Today it would be called a “walk-off” win but that expression wasn’t in vogue on July 25, 1956. In any event, contemporary accounts reveal the winning team didn’t exit the field by walking off. They were too busy mobbing the young hero.

Don’t stop me now

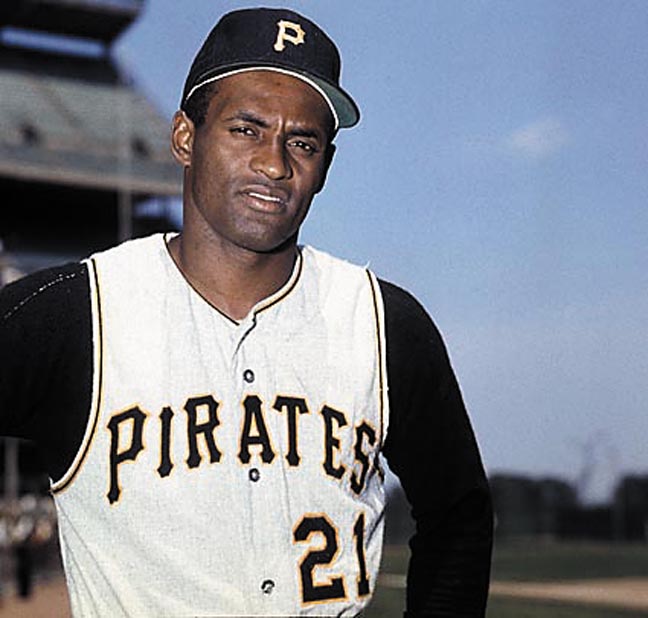

On that day, the visiting Chicago Cubs went into the bottom of the ninth inning at Forbes Fields leading the Pittsburgh Pirates, 8-5. Turk Lown took the mound and walked Hank Foiles, surrendered a single to Bill Virdon and walked Dick Cole to load the bases with no outs. Next up was the Pirates’ 21-year-old future star Roberto Clemente, in only his second year in the majors. Jim Brosnan was brought in from the bullpen to replace Lown. His first pitch to Clemente came in hard, high and inside. Clemente belted it deep into left field against the light standard. Left fielder Jim King backed up to catch the ball, but it was too high and caromed toward center field. By the time center fielder Solly Drake tracked it down, the three baserunners had scored. Clemente was approaching third as the ball came to the relay man, Ernie Banks.

Manager Bobby Bragan, coaching third base, held up his arms, yelling in English and Spanish for Clemente to stop there. The speedy Clemente disregarded the stop sign, motored toward home, slid past the plate and touched it with his hand before being tagged, having hit the first — and to this day still the only — game-ending inside-the-park grand slam in baseball history.

“Fine him? Definitely not.”

After the game, Bragan said, “I knew we had the game tied and I was afraid Clemente would be thrown out at the plate. At that stage, I wanted to play it safe with the winning run on third and none out. But Clemente evidently didn’t hear me or had his mind made up he could go all the way.”

Of course, Bragan’s reasoning was sound. Clemente’s explanation made no sense. “The game is over if I win,” he said. “So I just run and I know I can score.” Then again, at the time he was a raw talent still learning the game.

For Bragan, it was all good, as the expression goes today. “Fine him?” said Bragan, repeating a reporter’s question. “Definitely not. He’s winning for us, isn’t he?”

An unforgettable eight days

I wanted to start with one of my favorite Clemente stories, as we in Pittsburgh are in the midst of the 50th anniversary of an unforgettable eight-day stretch that began on December 23, 1972 with Franco Harris’s “Immaculate Reception,” a shoestring grab of a deflected football on fourth down and subsequent touchdown run with five seconds to play in the game, giving the Pittsburgh Steelers a 13-7 playoff victory over the stunned Oakland Raiders at Three Rivers Stadium, and ended the following New Year’s Eve with the death of the 38-year-old Clemente in an airplane crash while on a mercy mission to deliver relief supplies to Nicaragua. Much will be written about these events over the coming days. Sports writers are mandated to commemorate every anniversary that ends with a zero. It’s the second thing we’re taught as sports writers, right after we learn the secret handshake.

“Give the kid the ball!”

Everybody who ever encountered Clemente or Harris has always come away feeling good about it. George R. Skornickel describes one such encounter in his 2010 book, Beat ‘Em Bucs: The 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates. As a child, Skornickel liked to stand along the railing at Forbes Field near the Pirates’ dugout, where one might get an autograph, before the game. He arrived early one day for pregame warm-ups and observed Clemente playing catch with Joe Christopher. As the players exited the field, young Skornickel’s eyes met Clemente’s and Clemente tossed him the ball.

However, Skornickel was hit from behind, catching his balance in time to see a large man grab the ball. With tears in his eyes, he heard a loud voice yelling, “Give the kid the ball!” There was Clemente, about to leap over the railing and chase down the adult ball-thief, who then gave up the ball. Clemente, genuinely concerned, his foot still on the rail, yelled, “Kid, are you all right?” Skornickel nodded his head and slowly approached Clemente, who asked, “Are you sure you’re OK?” Clemente would sign the ball before heading into the dugout.

The last time

The last time I saw Clemente in person was a Saturday afternoon, July 1, 1972, against the Cubs and pitcher Fergie Jenkins. The big right-hander pitched a perfect game through five innings. In the sixth, he gave up three hits, but thanks to a double play, held onto a 1-0 lead.

Leading off the bottom of the seventh, Clemente strode to the plate, doing his familiar neck stretches. There was an air about him that said, that’s enough of this nonsense. Sure enough, he drove a pitch over the left field wall for a game-tying home run.

However, the Cubs would take a 3-2 lead into the bottom of the ninth. Milt May, pinch hitting for Jose Pagan, led off with a single off Jenkins. Clemente followed and promptly hit his second homer of the day, a long drive over the center field wall to win the game, 4-3, sending the fans home delirious with joy and rendering Jenkins and the Cubs shell-shocked.

Although I attended a few more games in 1972, somehow I managed to pick games when Clemente was being rested. There was nothing more disappointing for a 14-year-old Pirates fan than to take his seat in right field and see Vic Davalillo trot out to man the position.

The biggest lies?

I can count on one hand the number of times my father took me to sporting events, but he could sure pick them! We were together at Three Rivers Stadium to see Clemente hit those two homers and later for the Immaculate Reception. It’s said the four biggest lies in Pittsburgh are, in no particular order:

- The check’s in the mail.

- I was there when Bill Mazeroski hit the home run to beat the New York Yankees in game seven of the 1960 World Series.

- I was there during the Immaculate Reception.

- I was there during the Immaculate Reception and actually saw it.

I’m about to tell you one of those lies, except for me, it will be true.

At that Steelers-Raiders playoff game, most fans, including Dad, looked at the ground when the Raiders’ hard-hitting safety Jack Tatum broke up Terry Bradshaw‘s desperate pass and missed seeing Franco (we’re on a first-name basis with Harris here in Pittsburgh) grab the ball. I kept my eyes on the field and saw Franco run to the floating ball like a center fielder toward a sinking line drive, catch it in stride and ramble into the end zone past the stunned Raiders secondary.

Passings

I remember learning of Clemente’s death on New Year’s Day, 1973, in the car as the family was on their way to Mass for the Solemnity of Mary. The man on the car radio reported Clemente was dead. I was in a state of shock after that. The man then droned on about Watergate. Or maybe it was the war in Vietnam. Or maybe the 1973 model Ford Pinto’s new options. I really can’t remember. Nothing registered at Mass either. To me the priest sounded like the teacher on the Peanuts cartoons: “Wah wah wah wah wah wah.”

Now comes the news that Franco passed away on December 20. On Christmas Eve, he was to be honored at Acrisure Stadium at halftime of the game between the Steelers and the Raiders. His number 32 would be retired and the Immaculate Reception would be commemorated. It reminds me Willie Stargell died in the morning of the day the Pirates were to unveil his statue at PNC Park. Stargell and Harris were my two favorite Pittsburgh athletes.