It’s official. I’m old. I’m used to the baseball players I admired as a youngster grousing about how the game was better in the “old days.” Now one of my kids’ heroes is doing it.

Outside of the Bronx, I’d venture a guess most baseball fans are Yankee haters. But what self-respecting baseball fan couldn’t love watching Paul O’Neill, the erstwhile Cincinnati Red and New York Yankee right fielder, owner of five World Series rings? You had to love his intensity. You had to love the “relentless pursuit of perfection,” to borrow a phrase from his plaque at Yankee Stadium. O’Neill thought he should bat 1.000. He never gave a pitcher credit for getting him out. He cared about winning more than he cared about his personal statistics. You never saw him standing on first base, yukking it up with the opposing first baseman. He was always deeply engaged and played the game the right way. You never saw him dancing around the bases after hitting a home run.

O’Neill’s hitting philosophy

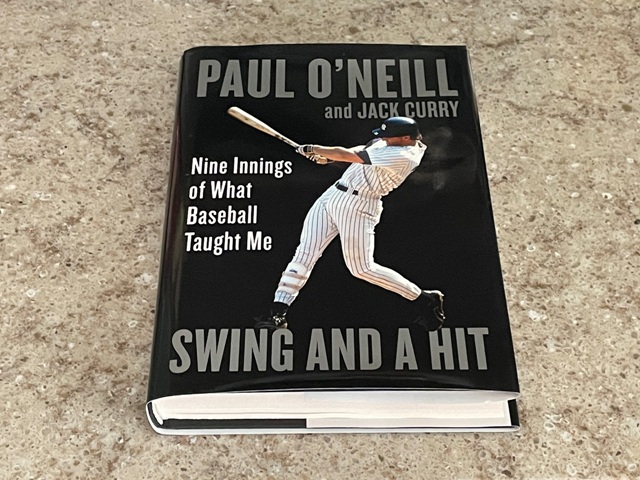

O’Neill doesn’t care for how today’s hitters approach their craft. He writes all about it in Swing and a Hit, co-written with Jack Curry. The book contains some redundancy; O’Neill admits as much on page 202. Unless one is completely devoid of reading comprehension skills, one will quickly learn O’Neill’s hitting philosophy. He hated to strike out. He hunted fast balls. His swing was level with a slight uppercut finish. He wanted to hit line drives. He tried to hit to all fields. Despite the redundancy and the notion that a book on hitting by O’Neill may not carry the same cachet as The Science of Hitting by Ted Williams, it’s interesting reading nonetheless.

While O’Neill gives the reader a peek at the personalities of teammates like Bernie Williams, Derek Jeter and Don Mattingly, what you won’t find are controversy and juicy clubhouse gossip. Then again, O’Neill played for the calm, staid Yankees of Joe Torre, not the volatile Yankees of Billy Martin. Maybe there wasn’t much to tell.

Charlie Hustle and Sweet Lou

The first two chapters discuss a pair of competitors who were essentially O’Neill’s first two managers with the Reds, Pete Rose and Lou Piniella. (Tommy Helms had briefly been the interim manager in 1989 when Rose was banned from baseball.) Rose left O’Neill alone and told him just to be the kind of hitter he can be. As you might imagine, O’Neill liked playing for “Charlie Hustle.” On the other hand, O’Neill didn’t see eye-to-eye with Piniella, who wanted him to hit more home runs. With prodding from “Sweet Lou,” O’Neill reached a career high in homers with 28 in 1991. But O’Neill was displeased with his .256 average and 107 strikeouts.

Finally, the Reds traded O’Neill to the Yankees before the 1993 season. Piniella would become the manager of the Seattle Mariners, thus beginning an ongoing war between player and former manager due to the constant intimidation tactics against O’Neill by the Mariners pitchers. O’Neill takes the high road, saying no matter their differences, he respected Piniella as a competitor and knows he was only trying to help during his time with the Reds. But you can bet Piniella isn’t on O’Neill’s Christmas card list.

No easy game

There’s a chapter on why he loves to watch DJ LeMahieu hit as opposed to the guys who swing for the fences every time up or stubbornly hit into the shift time after time. That chapter resonated with me. I, too, prefer to watch a hitter like LeMahieu or Luis Arraez, versus, say, Javier Baez. When Baez steps up to the plate, that’s when I get up and go to the refrigerator for a snack.

The book is sprinkled with quotes from opposing players. As you might imagine, all are complementary to O’Neill as a hitter and fierce competitor. Hey, it’s his book and he can print what he wants. O’Neill recounts some of his successful at-bats in important games. However, he also devotes an entire interesting chapter to the pitchers who gave him the most trouble — Randy Johnson, Jesse Orosco and Al Leiter.

Perhaps because he recognizes how difficult the game is and worked so hard to be good at it, O’Neill is in awe of the legends of baseball. He sits in disbelief while speaking with Ted Williams on the phone. He’s proud of a childhood photo taken at old Crosley Field, with the great Roberto Clemente in the background.

Those Yankee years

O’Neill leaves the subject of hitting for a couple of long chapters about his Yankee career and their many big postseason games. There’s not a lot of inside stuff there but he does get into what he was thinking and how he approached his at-bats. Nor is much space devoted to the 1990 World Series, when he got his first ring as a Red. Heck, having played in so many World Series, it’s amazing he remembers any details at all. He theorizes if the 1998 Yankees weren’t the best team in the history of baseball, they were the most perfectly constructed roster. We read of Torre’s steady hand and wonder why he was fired from three previous managerial posts.

The dominance of that 1998 Yankees team baffled me because they were so bereft of superstars. They were a combination of a lot of very good players, each of whose presence alone wouldn’t have elevated a losing team very much. The whole was better than the sum of the parts. Reading about their devotion to winning and playing the game the right way gave me a little more insight into what made them tick.

In any event, Swing and a Hit is at its best when the subject is hitting. O’Neill articulates his points unambiguously without getting overly technical.