The Cleveland Indians last won a World Series in 1948, defeating the Boston Braves in six games. In fact, the 1948 championship will now be forever known as the last one won by the Indians. The franchise will operate under a new name in 2022. It’s been an astounding 73-year drought for Cleveland baseball. Now that the Boston Red Sox and the two Chicago teams have won World Series during the past two decades, the Indians would qualify as the worst sports franchise of my lifetime but for the existence of the Detroit Lions.

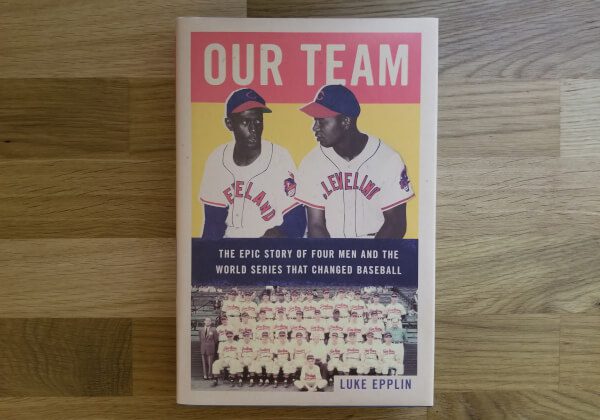

The 1948 Series was an anomaly in the midst of a period dominated by the New York Yankees, Brooklyn Dodgers and St. Louis Cardinals. Perhaps that’s why it’s been sadly under-documented. That is, until 2021 saw the release of Our Team by writer Luke Epplin.

It’s an important World Series in that it was the first Series won by a team with Black players. Epplin’s story centers around four key figures, all of whom are vividly portrayed.

The hustler

In 1941, 27-year-old Bill Veeck bought the minor league Milwaukee Brewers, turning it into the hottest ticket in town with his wacky promotions. However, with World War II raging, Veeck enlisted in the Marines, eventually losing a leg in battle. After returning home, he sold the Brewers and in 1946, purchased the Indians.

Attendance at Indians games was lackluster. Veeck revived interest among Clevelanders with the same kind of off-the-wall promotions that had worked with the Brewers. A tireless promoter, Veeck roamed the stands to meet fans and kept a whirlwind schedule of speaking engagements against doctor’s orders.

Veeck knew, however, the promotions would work only for so long. Eventually the team needed to become winners to sustain the interest he had built. He continued wheeling and dealing to bring in the players he needed to make it happen. If it meant breaking the color barrier in the American League, so be it. In the end, Veeck was as responsible for the championship as any uniformed personnel.

The phenom turned businessman

Bob Feller‘s was the type of story baseball scribes loved in the 1930s. Raised on an Iowa farm, his father had converted a patch of farmland into a baseball diamond where Feller could hone his pitching skills, often against older competition. Feller would join the Indians in 1936 at the age of 17. In 1938, he began a streak where he led the American League in strikeouts for four consecutive years. He also led the league in walks in three of those years. Most importantly, he won 76 games from 1939-41 before World War II interrupted his career.

Anybody who believes yesteryear’s athletes played simply for the love of the game needs to learn more about Feller. Feller earned what were thought to be high salaries for the era. A publicity photo showed Veeck fretting while Feller sat an adding machine, calculating his earnings. Additionally, Feller organized annual offseason barnstorming tours, which were more lucrative than his job with the Indians. He was often accused, rightly or wrongly, of prioritizing his barnstorming tours over the Indians’ seasons.

By 1948, it was thought the relentless barnstorming was taking its toll and affecting his performance with Cleveland. In that season, he still won 19 games and led the league in strikeouts. However, he also lost 15 and his 3.56 ERA was his highest since he was 19 years old. In the Series, Feller went 0-2 and surrendered eight runs in 14-1/3 innings in two starts. This included a poor game five performance when he could have wrapped it up in front of the home fans. After the Indians won game six, his teammates celebrated as Feller sat in front of his locker, frustrated and sad.

The quiet man

Veeck chose Larry Doby, a second baseman from the Newark Eagles, to break the color barrier in the American League. Doby made his debut as a pinch hitter on July 5, 1947, less than three months after Jackie Robinson debuted with the Dodgers. Indians manager Lou Boudreau didn’t seem to want Doby as much as Veeck did, however. Doby was employed mostly as a pinch hitter in 1947. The few times he played in the field, he was moved all over the infield. Doby had just five hits over 32 official at-bats.

His teammates didn’t seem to want him any more than did Boudreau. The season was a struggle for the quiet 23-year-old, who would later point out that while much had been made, rightfully so, of the challenges Jackie Robinson faced in 1947, it wasn’t as if things were easier for the second Black major-leaguer.

Veeck still believed in Doby, however. In the spring of 1948, the Indians converted Doby to an outfielder. He began to shine, offensively and defensively. The reluctant Boudreau had to concede that Doby now deserved to be in the everyday lineup.

It paid off in the World Series, with Doby delivering the winning two-run homer in the pivotal game four. Winning pitcher Steve Gromek grinned and hugged Doby in an iconic photo that ran in newspapers all over the country.

The veteran

In the middle of the season, Veeck sensed the starting rotation needed bolstering and knew just the man. He acquired long-time Negro Leaguer Satchel Paige, whose major league debut was long overdue. Although officially age 42 in 1948 and perhaps even older, Paige still threw hard and had pinpoint control. (Paige liked his money, too, deserting the Kansas City Monarchs during the 1946 Negro League World Series to join Feller’s barnstorming tour.)

Paige debuted for the Indians on July 9, 1948 and provided the boost they needed. As a starter and reliever, he went 6-1 over 16 appearances in July and August. That was the record he finished the year with. After beginning September with a rough start against the St. Louis Browns, he was seldom used for the remainder of the regular season. In the World Series, Paige appeared in just one game, a mop-up role in game five, a fact over which he remained bitter.

Doby and Paige roomed together on the road but didn’t see eye-to-eye and weren’t friends. The dignified Doby felt Paige acted too much like a caricature before their white teammates. In the end, Doby and Paige come across as sad characters, Doby because he never felt accepted by white teammates and opponents, Paige because he never got a chance in the major leagues until he got old.

The book

Epplin does a fine job crafting the story of the four men and the Indians’ storied season. If he’d asked my opinion, I might have suggested adding a fifth in Boudreau, the manager Veeck tried to trade in 1947.

Only Eddie Robinson, who recently passed away at the age of 100, was still alive among the players on the participating teams and available for interviews. For quotes from the other participants, Epplin relied on newspapers, magazines and books. Often when I read books that used such sources to get quotes, I can’t help but think I’m reading remarks the speakers sanitized for publication. Not so with Our Team. One gets the feeling the subjects were speaking frankly in the quotes unearthed by Epplin’s meticulous research.

Unlike, say, David Halberstam’s October, 1964, which covers both World Series participants equally, we don’t learn anything about the Braves until we get to the World Series. Up to that point, the focus is completely on the Indians. Then again, history is always written about the victors.