Of course, the easy answer is yes.

The Los Angeles Dodgers had a 19-14 record in Clayton Kershaw’s outings. This comes out to a .576 winning percentage, just a hair better than the team’s .568 overall winning percentage. Regardless, Kershaw was the best pitcher in baseball in 2013. His adjusted ERA of 194 was easily the best mark in baseball, and you have to go back to Zack Greinke in 2009 to find a mark that good.

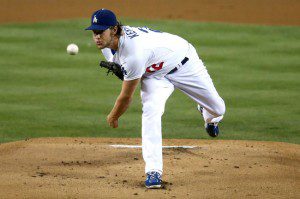

Before we get to the question, let’s look at how good Clayton Kershaw is:

Kershaw combines phenomenal peripheral stats with the rare ability to consistently beat these numbers by limiting hits on balls in play, suppressing homeruns, and stranding runners. He posted a 25.6 percent strikeout rate in 2013, the second best rate of his career. More importantly, Kershaw had a 5.7 percent walk rate that was the lowest of his career. The differential between the two was the 6th best in the MLB. His FIP– was the best in the NL, and only three NL pitchers could top his xFIP-.

So the peripherals are great.

However, with Clayton Kershaw, the story doesn’t end there. Since 2009, Kershaw’s BABIP is .264. If this was one or two season, I might call this an abnormality, or something that is bound to regress. But we’re talking about a sample of over 2700 balls in play. It’s not just the Dodgers defense either, Kershaw’s BABIP is 20 points lower than the team average over that span. Combine that with all Kershaw’s strikeouts, and opponents hit just .192 against him in 2013.

Clayton Kershaw also maintains a consistently low HR/FB ratio. His 6.2 percent HR/FB ratio since 2009 is bested only by Dallas Braden‘s 6.0 percent. Pitching in the cavernous Dodger Stadium helps, but this number jumps by less than one point on the road. His 0.52 HR/9 since 2009 is the lowest in the MLB, and only Matt Harvey beat the 0.42 HR/9 he posted in 2013.

Aided by his ability to control the running game, Clayton Kershaw consistently strands runners at a much higher rate than the league average. Runners have stolen only 48 bases in 90 attempts with Kershaw on the hill. The combination of these factors enables him to maintain an ERA that is significantly lower than his already excellent FIP and xFIP.

So, with that being said, do the Atlanta Braves or whoever Clayton Kershaw’s next postseason opponent may be have any chance at beating him?

The first order of business is to remove as many lefthanded hitters as possible from the lineup. Lefties managed a .477 OPS and two homeruns against Kershaw in 2013. Meanwhile, they struck out in 41.5 percent of their plate appearances, whiffing on nearly 20 percent of their swings. Noted lefty killer Francisco Liriano struck out 26.8 percent of lefthanded hitters. In Game 1 against the Braves, lefthanded hitters Freddie Freeman, Jason Heyward, and Brian McCann combined for a 1-8 showing with one walk and four strikeouts.

Like Liriano, Kershaw has a nasty slider. A look at BrooksBaseball reveals just how dominant it is. Lefties whiff on more than 25 percent of Kershaw’s sliders, and on nearly half their swings. Against the Braves it fared even better. Righties don’t do too well either, but at least they put up a fight, making more contact, and hitting more line drives and fly balls. Unlike Liriano, Kershaw also has a 12-6 curveball, which generates nearly the same results as his slider.

While Kershaw’s devastating curveball and slider are even more effective against lefthanded hitters, the difference on his fastball is more drastic. Lefties whiff on 16 percent of his fastballs, compared to just 4.8 percent for righties.

Kershaw uses his changeup, his fourth best pitch, exclusively against righties. The whiff rate on the change is only 8.6 percent, and it resulted in a strike on just 42 percent of pitches, compared to 67 percent for his other pitches. All told, righthanded hitters had a .532 OPS against Kershaw in 2013. Far from promising, but certainly better than what lefties can manage.

He’s pretty close to the perfect pitcher, but Clayton Kershaw can be beaten. But if your team leans heavily on lefthanded hitters, there’s even less hope.