What does it mean to be the best?

Tina Turner thought it was a simple matter. But this author begs to disagree, especially when it comes to pitching. The Cy Young officially brands itself as an award given to the best pitcher in the American and National Leagues.

What the heck does that mean?

This is a particularly important question this season. First, Shohei Ohtani is redefining what it means to be dominant. But in addition, debates about pitcher value and how long starters should stay in games have changed what the ideal outing looks like. Plus, we’re seeing an historic revolution in the importance of bullpens.

We can consider the rightful winners of the Cy Young by looking at some contenders and asking whether or not they fit the label.

Should Shohei Ohtani win the AL Cy Young?

We begin with easily the most challenging topic. It has been impossible to miss the rise of Ohtani. He leads Major League Baseball in bWAR, and it’s not close. His formula for success is simple: be a pitcher with an ERA below three while raking more than 40 home runs. What’s so hard about that?

Ohtani’s biggest competition is New York’s Gerrit Cole, a familiar face who is on a tear again this season. Cole has the lowest rate of hits allowed while also commanding the highest strikeout rate among AL pitchers. He also boasts a lower ERA than Ohtani (2.73 compared to 2.97) and a better WHIP (0.968 versus 1.071).

But Ohtani beats out Cole in a number of categories – namely, home runs hit (42 to zero) and hits (117 to, again, zero). This is obvious. Cole hasn’t even registered an at-bat in the 2021 season. Everyone knows this.

The question is whether offense contributions supplement your resume as a pitcher. This has rarely been an issue. Sure, Madison Bumgarner hits a few every season, but he never leads the league. Most of us tacitly accept that batting is not a factor for pitchers, especially in the AL. Why? Just because pitchers don’t usually hit well? It may make more sense in the AL, since a pitcher’s team can employ a designated hitter who almost assuredly hits better than the pitcher does.

Ohtani is making us rethink this. What happens when the pitcher hits better than not only their team’s DH but every DH in the league? Does that count for something?

In the eyes of Cy Young voters, it almost definitely does not. Most articles online don’t even mention Ohtani in a Cy Young context. They prefer Cole and others like Lance Lynn of the White Sox. But this is a year that should make us reflect on how we consider offensive production in how good a pitcher is. Pitchers contribute in more places than the rubber, just like a shortstop contributes more than they do covering the middle infield.

Should Corbin Burnes win the NL Cy Young?

We turn now to an issue that resulted from the analytics revolution. Recent data suggests that starting pitchers are better off not pressing their luck. After batters have seen the same pitcher twice, the pitcher’s effectiveness can drop rapidly. This is known as the Times Through The Order Principle, or TTOP (no, TTOP doesn’t stand for Teen-Titans-Only Party). The TTOP reared its head in the playoffs last year when the Rays manager, Kevin Cash, pulled Blake Snell after the lefty pitched five-and-a-third innings and allowed no runs. While Cash did not apply the TTOP accurately here for a few reasons, it introduced many viewers to the concept.

The consequences of the TTOP are manifold. First, it suggests that, in close games, managers should be willing to pull starters quickly, as each run matters. This means that, going into the seventh inning in a close game, a manager may want to preemptively pull their ace in favor of a solid reliever. As such, pitchers pitching deep into games is less advisable.

Enter Corbin Burnes. The Brewers right-hander leads the NL in FIP, home runs allowed per nine and walks allowed per nine. He may not have the best case in the NL considering the Dodgers’ Walker Buehler has a lower ERA (2.05 versus 2.27), but analysts rarely give him even a passing thought.

Why? Well, Burnes has pitched 37 fewer innings than Buehler. But how much does the number of innings matter? Consider how easily this difference could result from the TTOP. Suppose the Brewers manager was more careful about allowing starters to go deep into games. Burnes has started 24 games. If his manager pulled him one inning earlier each game because he honored the TTOP more than the Dodgers manager, it accounts for more than half of the innings deficit. So, punishing pitchers for throwing fewer innings doesn’t make much sense now.

Frankly, it never made much sense before. Let’s suppose Burnes was a more valuable pitcher but pitched in a handful fewer games. Given that he’s available, he’s the best pitcher. Isn’t the Cy Young supposed to go to the “best pitcher”? The gap is arbitrary, too. How many fewer innings can a pitcher pitch before voters decide that he’s out of the running?

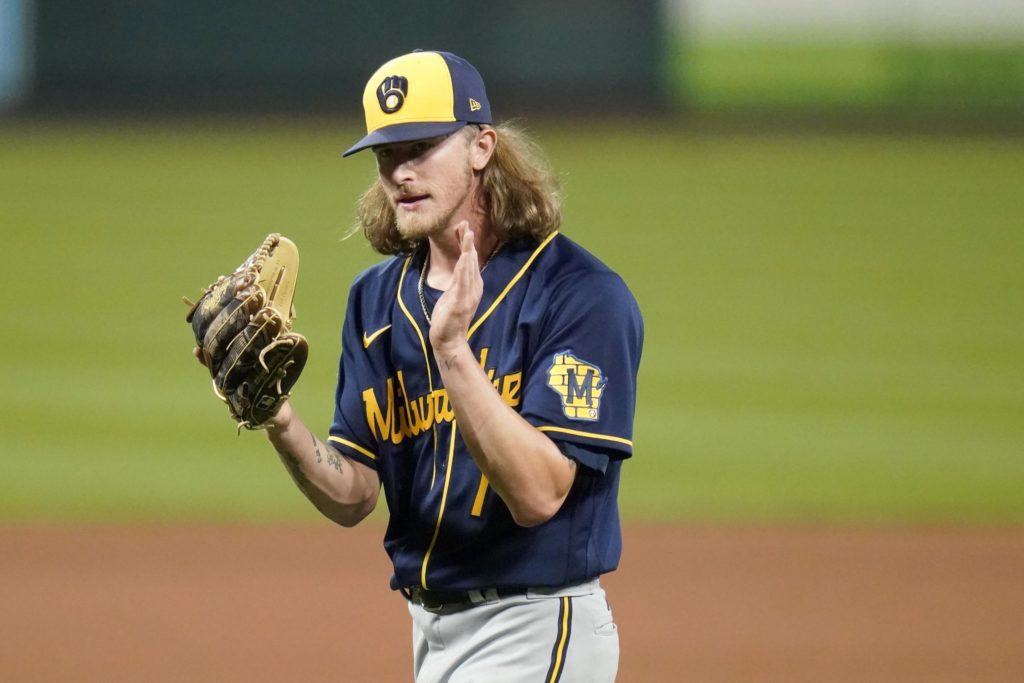

Should Josh Hader win the NL Cy Young?

Now here is a controversial topic.

ESPN recently published an article predicting the final month of the season, including who their baseball writers think will win the major awards. Their NL Cy Young revealed a fun twist: 12 votes for Buehler, two for Burnes, two for the Phillies’ Zach Wheeler and one for Josh Hader, the Brewers reliever.

The one vote came from Doug Glanville, and his rationale is simple. We live in an era of change. Starters are pitching less than they ever have – the White Sox’s Lynn averages fewer than six innings pitched per start. As such, relievers are more important now than they ever have been. Is there a better reliever than Josh Hader?

It’s hard to find one. He wields an ERA of 1.48 with a WHIP of 0.801. He’s finished 34 games for the Brewers with 29 saves. His team leads their division, if that matters for anyone.

This is part of a larger trend that dates back to Zach Britton. The former Oriole finished fourth in the 2016 Cy Young voting as a closer. His numbers were pure madness: an ERA of 0.54 with 47 saves (though his WHIP was actually higher than Hader’s at 0.836). The fact that Britton even pierced the top five was a subject of intense controversy, and that was five years ago. Hader receiving sizable votes would be a continuation of Britton’s legacy.

It would spit in the face of voting trends, though. No reliever has won a Cy Young since Eric Gagne in 2003. This was not always the case. Between 1974 and 1992, a reliever won the trophy eight times. Often, these seasons were of a lower quality than what Hader has delivered. Dennis Eckersley won in 1992 with an ERA+ of 195. This season, Hader’s ERA+ is 286. (Astonishingly, Britton’s 2016 ERA+ was 803.) The bar is clearly higher now than it ever was before. Not even with dominance will voters hand the trophy to a bullpen arm.

Glanville’s point is still strong. Hader’s stats warrant votes in any era, but now that relievers are more valuable (and often contribute an outsized amount in the playoffs), his numbers should spur real conversation.

Now what?

This article is highly unlikely to change the minds of BBWAA. I’m not even advocating for one Cy Young winner over another. My only aim is to ask you, the reader, to think about what you think matters in determining who the “best” pitcher is. Then, ask yourself why you think that.