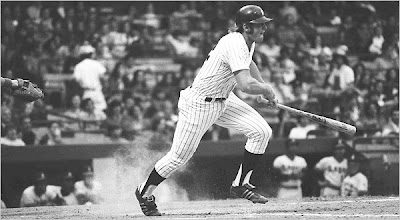

He was a gifted Jewish multi-sport athlete from Atlanta and a former first-round draft choice of the New York Yankees. Being in the right place at the right time, Ron Blomberg made history 40 years ago on opening day, April 6, 1973. No home run or hit was necessary. For the “Boomer,” simply stepping into the batter’s box changed the game of baseball forever.

That weekend, the Yankees played the Boston Red Sox at Fenway Park. At 1:53 p.m. on a cold, windy day, Blomberg was the first of the afternoon’s “designated pinch-hitters” across the American league to come to the plate. He drew a bases-loaded walk courtesy of Louis Tiant, giving New York a 1-0 lead.

Blomberg had been informed that he was batting sixth in the lineup and playing DH earlier on the flight north to Boston. It was Yankees manager Ralph Houk and the coaching staff who broke the news.

“Skipper, I don’t really know much about it, what do I do?” asked the 24-year-old kid, who been an outfielder for most of his young career.

Houk’s response was simple, yet forever controversial: “You’re basically pinch-hitting for the pitcher four times in a game.”

Baseball was not in a good way in 1973. Labor and pension disputes over the previous winter increased disgust among fans. Other sports, such as drag racing, skiing, golf, hockey and basketball turned television viewers away from the national pastime. Football, especially, was becoming America’s game.

The cultural, not just political, landscape was changing for the worse. Sporting News scribe Furman Bisher wrote that, “Baseball is developing all the appeal of coal mining.”

It is against this backdrop that the game itself underwent radical changes. Out of the 1973 winter meetings, a “basic agreement” was reached among owners and the players association. This included an agreement on a minimum salary, right to arbitration and a new 10-5 rule, in which a full no trade clause was given to a player who had at least 10 years of major-league service time, five with his current team.

Out of those meetings also came what is perhaps the most radical and controversial change to the game in baseball history. The owners of American League adopted a three-year experiment of a “designated pinch-hitter,” Such a hitter would bat in place of the pitcher. It was the most significant change the game had seen since 1901, when it was ruled by the National League that a two-strike foul ball was not a strikeout (The AL adopted this rule two years later).

By an 8-4 vote, the American League approved the measure for a designated hitter, hoping to see an increase in both offense and fan attendance. Of course, it was also a business decision. More fans meant more revenue.

The National League refused to participate, with “purists” unwilling to make such a radical change to the game. Besides, in the years leading up to the vote, the senior circuit had enjoyed better attendance.

The new Rule 6.10 stated, “A hitter may be designated to bat for the starting pitcher and all subsequent pitchers in any game without otherwise affecting the status of the pitcher(s) in the game.”

Oakland A’s owner Charlie Finley was an early ardent supporter of this rule. He said that the “average fan comes to see action, home runs … I can’t think of anything more boring than to see a pitcher come to bat, when the average pitcher can’t hit my grandmother … Let’s have a permanent pinch-hitter for the pitcher.”

“It has certainly eliminated the dead inning,” said Houk. “… and it makes the games more exciting because a rally is more possible in any inning.”

The DH also extended the careers of aging players who were no longer able to field their position during the rigors of a long season.

Mickey Mantle was part of the camp of traditionalists. “It’s the records, (he said) people are always talking about the records, and if you eliminate the records, the game loses a lot of its romance.”

“It’s legalized manslaughter,” said Red Sox star Carl Yastrzemski. His argument was that the rule was now an open invitation for pitchers to throw at hitters, since they didn’t have to step into the batter’s box themselves.

Baltimore Orioles manager Earl Weaver also opposed the new rule, arguing that the strategy of the game was lost without a pitcher’s bat in the lineup.

“I might be from the old school, but I don’t think baseball needs saving. “

The idea for a designated hitter didn’t just come out of a vacuum. Philadelphia Athletics manager Connie Mack had suggested it as early as 1906. Ironically, when National League president John Heydler brought up the idea to speed up the game, American League management turned him down.

In 1969, the International league briefly implemented the use of a hitter batting for the pitcher. Although it was an optional rule, all of the league’s managers chose to follow it.

At the major-league level, with both the National League and American League’s approval, the DH was actually used in two spring training games in 1969. Commissioner Bowie Kuhn welcomed the new rule, but it would still take another four years until it was implemented during the regular season.

Blomberg had been chosen to DH that day for a couple of reasons. First, he had a slight hamstring injury as spring training drew to a close. Secondly, Houk wanted to use his left-handed bat in the line-up against the Sox’ right-handed Tiant.

The Yankees took a 3-0 lead in the first inning, but the Red Sox were victorious, 15-5, by days end, banging out 20 hits. Blomberg was 1-for-3 for the game, with a broken-bat single, and an RBI on his famous sacks full base-on-balls.

Ironically, Blomberg would go on to play 41 games at first base for the Yanks in ’73, and not serve as the team’s primary designated hitter. A mere 11 days after the season opener, third baseman Jim Ray Hart was acquired from the San Francisco Giants to fill that role full-time. In 106 games for the Bronx Bombers, Hart batted .256 with 12 home runs and 50 RBI.

Orlando Cepeda was the only player on either roster on April 6 who was signed just to hit a baseball. “Cha Cha” or “Baby Bull,” as he was known, was an offseason gamble by the Red Sox, given his bad 35-year-old knees. Sox GM Dick O’Donnell signed the former National League Rookie of the Year to an $80,000 contract, including a Mercedes as a signing bonus. Ironically, Blomberg got all the glory while Cepeda was a rather quiet 0-for-6.

Years later Ron reflected: “By all rights, Boston’s Orlando Cepeda should have been the first DH. … He was acquired by the Red Sox to be (their) full-time DH just one week after the rule was adopted. I was an accidental DH. But history smiled on me that day, as my teammates loaded the bases with two outs in the top of the first, bringing me to the plate for an historic at-bat.”

Blomberg’s big-league career lasted five more seasons until 1979, when the Chicago White Sox released him at the end of spring training. Lifetime, he hit .293/. 360/. 473, with 52 homers and 224 RBI.

1976 marked the end of the designated hitter “experiment,” and the American League adopted the change permanently. There had been a spike in both offense and attendance from the year before the change.

However, with two leagues with different rules, things got rather complicated, particularly when it came to the NL/AL team matchups in the Fall Classic, interleague play, and the All-Star Game.

Between 1976 and through 1984, the DH was used every World Series in alternating seasons. Beginning with the classic 1986 Mets-Red Sox matchup, come October, the DH would now be permanently used in every National League Park.

In ’76, Dan Driesssen became the first National Leaguer to assume the DH role, while in 2009; the Yankees’ Hideki Matsui became the first designated hitter to win World Series MVP. “Godzilla” hit .615 (8-for-13), with three home runs and eight RBI in the six-game Fall Classic versus the Philadelphia Phillies.

As for the All-Star Game, 1989 was when the rule was first applied to American League parks. In 2010, it was agreed upon by Major League Baseball that all parks, regardless of league affiliation, would make use of the designated hitter.

Interleague play began in 1997, and for the first time a National League team used a DH during the regular season.

Today, the designated hitter is used at virtually all levels of play, including parts of the minors, Japanese and amateur leagues, and colleges. As for the National League, it is becoming increasingly difficult to avoid someday adopting the rule. With the Houston Astros move to the American League West and an odd number of teams in each league, interleague games are being played somewhere every night.

To this day, his DH legacy never gets old for Blomberg. He is always at speaking engagements and serves as a good will ambassador for the team that drafted him in 1967.

“I had so much fun with this thing, because nobody can ever take this away from me,” says Blomberg. “…Because there’s not too many firsts in the game of baseball.”

Sources:

Swingin’ 73: Baseball’s Wildest Season, by Matthew Silverman. Lyons Press, Guilford, CT, 2013.

All Bat, No Glove: A History of the Designated Hitter, by G. Richard McKelvey. McFarland & Company, 2004.

Hammerin’ Hank, George Almighty & The Say Hey Kid: The Year that Changed Baseball Forever, by John Rosengren. Sourcebooks, Inc., Naperville, IL, 2008.

Big Hair and Plastic Grass: A Funky Ride Through Baseball and America In the Swinging ‘70s, by Dan Epstein. St. Martin’s Press, NY, 2010.

“The Designated Hitter Turns 40,” by Bill Littlefield from NPR’s Only A Game, April 6, 2013.

“Baseball’s Designated Hitter Rule Turns 40,” By Frank Daniels III, The Tennessean, April 6, 2013.

Baseball-reference.com

Baseball-almanac.com

.