The recent retirement of Tom Brady from football spawned discussions of his status as the GOAT (Greatest Of All Time). I’m here to discuss a different type of goat, specifically four goats in baseball history who, for me, never deserved the title.

Crazy 1908

The 1908 National League pennant race was the first exciting down-to-the-wire race in baseball history. The Chicago Cubs, New York Giants and Pittsburgh Pirates were virtually even all season long.

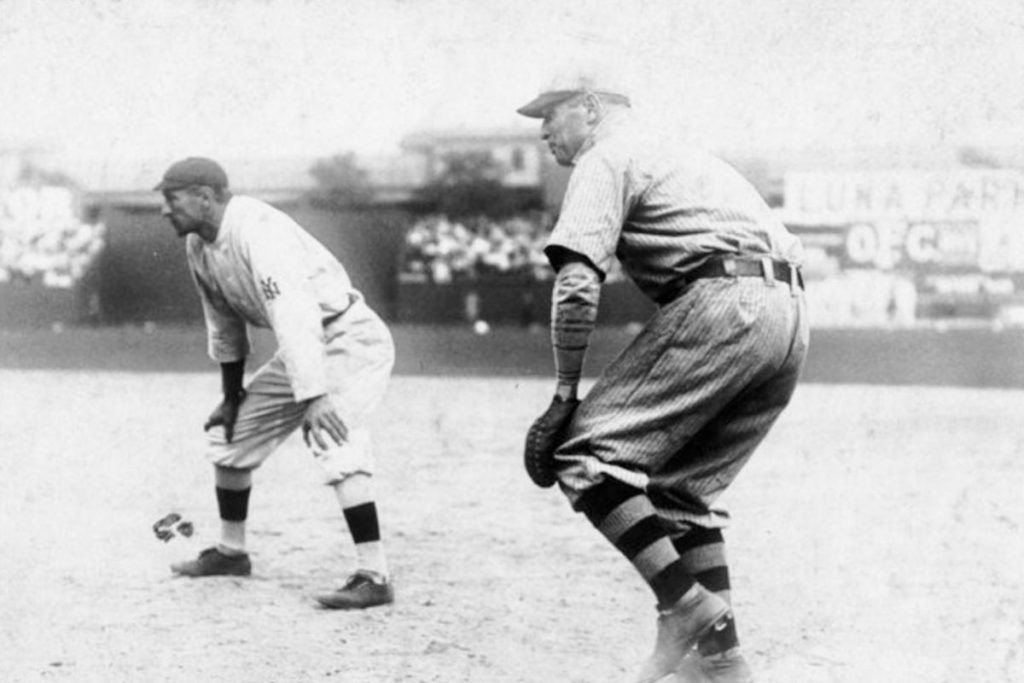

These were the Cubs of the Joe Tinker-to-Johnny Evers-to-Frank Chance double play combination immortalized in Franklin Pierce Adams’s 1910 poem, “Baseball’s Sad Lexicon.” The Pirates were led by future Hall of Famers Honus Wagner and Fred Clarke. Chance and Clarke were player/managers and perhaps the only two men in the Hall who qualify under either category. The Giants’ star was pitcher Christy Mathewson, who finished 1908 at 37-11. Mathewson was part of the Hall of Fame’s initial class.

The pennant race captivated the nation. Photos from the season show spectators standing along baselines and outfield walls, and even hanging from trees outside the ballparks. As the games concluded, fans rushed onto the field, causing the participants to exit the field as quickly as possible to avoid the chaos.

When the Pirates were playing on the road, back in Pittsburgh the fans stood outside the Pittsburgh Press building, waiting for a man to post the score of the day’s game on an outdoor bulletin board after each half-inning. On October 4, during a crucial game in Chicago, the crowd of Pirates fans waiting for updates stretched across Fifth Avenue from Grant Street to Market Street. For those of you unfamiliar with downtown Pittsburgh’s geography, that’s four blocks long.

Fred Merkle

Nineteen-year-old Fred Merkle, whose natural position was first base, made the Giants’ squad in spring training. It seemed manager John McGraw had big plans for him. In January, McGraw gushed to the legendary sportswriter Sam Crane, “Fred Merkle is much more than a first baseman, although he can play that position to the queen’s taste. On that last trip of ours last season Merkle showed to me that with practice he could fill any infield position as well as he can the initial cushion. I watched him closely — his every move, in fact — and I soon came to the conclusion that I had secured a genuine prize package.” (I can’t believe those were McGraw’s exact words.)

Alas, there wouldn’t be much playing time for the teenager in 1908. Before the season, the Giants acquired 14-year veteran first baseman Fred Tenney from the Boston Doves. Tenney would play in 156 games and lead the league with 690 plate appearances.

The case against Merkle

Merkle started just one game at the “initial cushion” in 1908. It was a fateful one. The date was September 23, with the 87-50 Giants hosting the 90-53 Cubs at the Polo Grounds. McGraw pressed Merkle into service when Tenney developed a case of lumbago. With the score tied, 1-1, in the bottom of the ninth, the Giants’ Art Devlin hit a one-out single off Cubs lefty Jack Pfiester. Moose McCormick’s grounder forced Devlin out at second. Merkle singled down the right field line, moving McCormick to third with the potential winning run. Al Bridwell hit a clean single to center, seemingly scoring McCormick. However, Merkle headed for the clubhouse rather than second base. Cubs center fielder Solly Hofman threw the ball toward second, where, after passing through the hands of several Giants, Cubs and spectators, Evers forced Merkle out.

Chance had alerted Umpire Hank O’Day to watch for the force play. Fans stormed the field, pounding on O’Day, who exited to safety without making a call on the field. Afterward, he told reporters that Merkle was out and McCormick’s run didn’t count. League President Harry Pulliam bizarrely declared the game a 1-1 tie, to be replayed on October 8, the season’s final day.

Both teams protested the decision. The Cubs argued the game should have been forfeited to them because the crowd on the field prevented its continuation. The Giants’ protest was based on the flimsy grounds that Merkle touched second. Pulliam denied both protests. The Giants and Cubs had identical 98-55 records going into that final game. (The Pirates at 98-56 had been eliminated.) The Cubs won the finale, 4-2, behind the pitching of Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown. Merkle was vilified as “Bonehead Merkle” for the rest of his life for costing the Giants the September 23 game.

In defense of Merkle

Again, in 1908 it was common for players and umpires to get off the field as soon as the game ended before being mobbed by fans. During what we today call a “walk-off” win (an expression I hate; how does the winning team leave the field when it doesn’t win in its final at-bat?), baserunners didn’t go through with what was seen as the formality of touching the next base. Umpires didn’t hang around to see whether they did.

There was precedent in Merkle’s favor as well. On September 4 at Pittsburgh’s Exposition Park, the Cubs and Pirates were scoreless in the bottom of the 10th. With bases loaded and two outs, the Pirates’ Owen Wilson stroked a single to center field off the Cubs’ Brown. The runner on first, Warren Gill, seeing the ball land safely and Clarke (the runner on third) touch home, turned around before reaching second and left the field.

Cubs center fielder Jimmy Slagle fired the ball to second for the force on Gill. Umpire O’Day was already at one of the benches, drinking water, back turned to the field. The Cubs tried to get O’Day’s attention, but he counted the run, saying, “Clarke has touched the plate.” Pulliam dismissed the Cubs’ protest, declaring, “I think the baseball public prefers to see games settled on the field and not in this office.” So it’s hard to say Merkle acted unreasonably.

Finally, let’s look at what happened after “The Merkle Game.” The Cubs went 9-2, while the Giants, with four double headers on their schedule, went 11-6, not good enough to catch the hot Cubs. The Cubs were the team of destiny, who played champion caliber baseball down the stretch. So let’s absolve Merkle of any blame for the failure of 1908.

Ernie Lombardi

Catcher Ernie Lombardi played in the Majors from 1931-47, mostly with the Cincinnati Reds. Before Joe Mauer came along, Lombardi was the only catcher to win more than one major-league batting title. My father, who was born in 1933, would tell me of Lombardi, one of the slowest runners in baseball history. Dad said when Lombardi came to bat, all of the infielders would shift into the outfield, knowing they could throw him out at first from there. As a Red, Lombardi won his first batting title and the Most Valuable Player Award in 1938 and was christened the goat of the 1939 World Series.

The case against Lombardi

In that Series, the New York Yankees were up, 3-0, in games. Game four, at Crosley Field in Cincinnati, was tied 4-4 at the end of regulation. In the top of the 10th inning with Bucky Walters on the mound, the Yankees’ Frank Crosetti led off with a walk and moved to second on a sacrifice bunt. Charlie Keller reached on an error, moving Crosetti to third. Joe DiMaggio followed with a single to right field. Crosetti scored easily as the ball went through right fielder Ival Goodman, who quickly retrieved it and fired home.

Keller and the ball arrived simultaneously. Keller collided into Lombardi, who lay near the plate, dazed, as DiMaggio made his way around the bases to score. Some accounts say Lombardi was briefly knocked unconscious. Others say Keller hit Lombardi where men don’t like to get hit. Lombardi, slow to recover, grabbed the ball and dove at DiMaggio, but not in time to prevent a third run. The Reds failed to score in the bottom of the 10th. The Yankees won, 7-4, sweeping the Series.

The play became known as “Lombardi’s Big Snooze.” Later in October, Henry McLemore of United Press, who I suspect was never involved in a violent home plate collision (for the record, neither have I), wrote, rather cruelly, “Lombardi . . . suddenly grew tired of life in the 10th inning of the final game of the World Series . . . and withdrew from it. Without a word of warning to his teammates or to the Yankees, he set up light-house-keeping at home plate, hung out a ‘please don’t disturb’ sign, and hibernated like the bear of a catcher he isn’t.”

In defense of Lombardi

In the end, DiMaggio’s run merely ensured the Reds would lose by three runs instead of two. The Reds also faced the Herculean task of coming back from a 3-0 deficit against the mighty Bronx Bombers. All things considered, it’s preposterous that history remembers Lombardi as the goat of the Series. I hereby absolve him as well.

Abrams out at home

I conclude with the case of reserve outfielder Cal Abrams and third base coach Milt Stock of the 1950 Brooklyn Dodgers. Tied with the Philadelphia Phillies for first place at season’s end, the Dodgers hosted a one-game play-off at Ebbets Field. Tied at 1-1 in the bottom of the ninth, Abrams led off against Robin Roberts with a walk. After failing at two bunt attempts, Pee Wee Reese singled to left field, moving Abrams to second. Duke Snider then dropped a short single to center field. Stock waved Abrams home, but Abrams was thrown out by Phillies center fielder Richie Ashburn, who was not known for a strong arm.

Eye witnesses in the Dodgers’ dugout and in the stands claimed Abrams took too wide a turn at third. Abrams denied this and claimed Stock’s signal was unclear, a tentative wave. There was also some thought that Stock failed to notice how shallow Ashburn was playing.

Regardless, with one out and Reese and Snider having each advanced an extra base on the throw home, Jackie Robinson was walked intentionally. Roberts then retired the next two batters without the run scoring.

In the 10th inning, the Phillies’ Dick Sisler hit a three-run homer off Don Newcombe to win the game and the pennant. After the season, the Dodgers fired Stock, along with manager Burt Shotton. The Dodgers traded Abrams during the 1952 season.

In defense of Abrams and Stock

Was it really such a bad move to send Abrams home? Although today’s analytics discount its usefulness, the conventional wisdom of the day would have been to have Snider bunt. With Abrams out at home, the Dodgers still had runners on second and third with one out. In other words, they were in the same position they would have been had Snider bunted. The batters who followed Robinson’s intentional pass, Carl Furillo and Gil Hodges, were paid to drive in runs but failed. Let’s remove the goat horns from Messrs. Abrams and Stock as well.