We’re neighbors, Peter and I, and he’s kind enough to sit down and chat with me now and again about writing, about baseball in general and the Rays in particular, about the publishing business, about our kids, about politics, about life in general.

We play in different sandboxes, Peter and I. He’s one of the great sports historians of the past 50 years, writing perceptive non-fiction bios and history books about everything from the Bums to the Bronx Zoo. Me, I more often write fiction, often short stories but also novels, usually about aliens and spaceships and the usual science-fiction stuff; but also, now and again, about baseball and its merits and demerits and how it does or doesn’t pertain to real life.

Golenbock’s sandbox is a lot bigger and better than mine, of course; and so I’m always happy to mostly listen and learn when we get together. We are, after all, both trying for the same thing: to discover essential truths about the game as we see it. He uses a lot research and countless hours of taped interviews (you should see his office shelves) to find the truth. Me, I do my best.

You’ve probably read some of Golenbock’s books and you probably have a favorite or two. Perhaps you liked the recent “George” (Wiley, 2009), a hard-hitting biography of George Steinbrenner; or perhaps his “In the Country of Brooklyn” (William Morrow, 2008); or maybe one of his earlier classics like “The Bronx Zoo” (Crown, 1979) with Sparky Lyle, or “Balls“ (Pocket, 1985) that he wrote with Graig Nettles.

I like them all, and I think of Golenbock as one of the hardest working researchers and best writers in the business. He knows his stuff when it comes to seeing things as they really are, though that’s sometimes a contentious thing to do in a sport that wraps itself in myth as much as baseball does. When it comes to our baseball heroes, let’s admit it, we don’t like hearing about those feet of clay. In fact, even when we know the truth we often don’t want to hear about it. We prefer the myth to the reality.

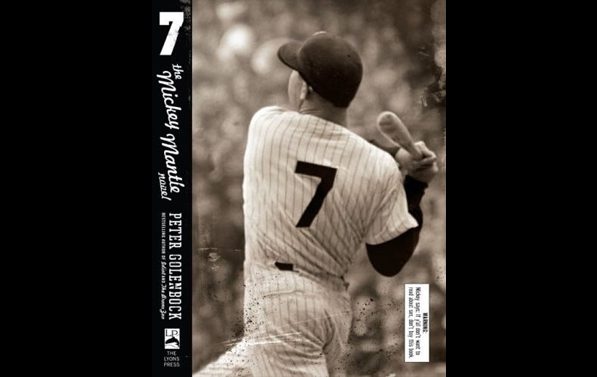

Ironically, Golenbock found out about that collision between myth and reality when he wrote a great piece of fiction, the novel “7,” which offered a fictional portrayal of the life and times of Mickey Mantle and his pal Billy Martin, a pair of alcoholic sex-addicts who have a ribald ramble through a very entertaining novel.

The premise of “7” is that the dead Mickey Mantle sits down in heaven’s version of Toots Shor’s bar with the equally dead sportswriter Leonard Shecter (an apt choice, since Shecter co-wrote the groundbreaking “Ball Four” with Jim Bouton) and tells the story of his life. Mantle is, by turns, hilarious, salacious, scandalous, offensive, sad and, ultimately, regretful.

The novel was caught up in the Judith Regan mess, when that editor’s Regan Books imprint was ended by HarperCollins after plans to publish O.J. Simpson’s “If I Did It” book caused a public outcry.

When it finally came out, the novel got some nice reviews. The St. Petersburg Times said it was “ultimately endearing,” and Baseballbookreview.com had nice things to say, including the warning to remember the novel is fiction.

But the New York press didn’t care for the novel. The New York Daily News called it blasphemous and The New York Times found it uneven, at best, and was disappointed that it didn’t, in the end, portray Mantle as a sympathetic character.

Me, I like the book, and I wonder if the Times read the same ending that I did. For me, “7” is an excellent look at a baseball hero so flawed that he allowed his many failings off the field to work to the detriment of his actions on the field. Mantle, of course, is just one of many ballplayers – and many athletes, in general – to treat their skills with a cavalier disregard. But in “7” we get an inside, if fictional, look at just how excessive the pampered life can be.

For me, there are two ways for a book to try and arrive at some essential truth about someone or something. One way is to accumulate enough small truths to build an accurate picture. Golenbock, in fact, did this with his book on Billy Martin — “Wide, High and Tight: The Life and Death of Billy Martin” (St. Martin’s Press, 1994) — about which Publishers Weekly said: “This is an extremely thorough and comprehensive biography of one of baseball’s most controversial figures.”

The other way is tell an accumulation of lies, things created from imagination or, sometimes, things that are fabricated versions of little realities, that make it all up before arriving at some essential truth. And this is what Golenbock does in “7,” creating a work of fiction, a novel, that ultimately arrives at an essential truth about Mantle and Martin, about baseball and some of its heroes, and about the myths we build about those heroes .

It’s interesting that, in the end, Golenbock is much kinder to Mantle in the novel than he is to Billy Martin in that biography. At the end of “Wide, High and Tight,” we see a Billy Martin who died stupidly, was probably at the wheel when his car crashed, and who paid an awful price for his excess. At the end of “7,” we see a penitent, if fictional, Mickey Mantle, who says, movingly, “When Marlyn and my boys read this took, maybe they’ll understand that fathers can be heroes, but heroes can’t always be fathers. And for that, I’m sorry. For eternity, I’ll be praying for their forgiveness. And yours.”

And that is, perhaps, as happy an ending to the Mantle story as one could wish for.

(Note: I’m working from the Advanced Reader Copy of “7,” which may contained minor deviations from the later published version).

Next: Dan Barry gets it right in “Bottom of the 33rd.”