How time flies. This July 31 marks the five-year anniversary of the Pittsburgh Pirates’ 2018 trade of outfielder Austin Meadows, pitcher Tyler Glasnow and a player to be named later (pitcher Shane Baz) to the Tampa Bay Rays for pitcher Chris Archer. It’s been called the worst trade in Pirates history.

The Archer deal was mentioned as a factor in general manager Neal Huntington’s dismissal after the 2019 season. But the worst trade in Pirates’ history? Not even close. My nomination for this dubious distinction follows.

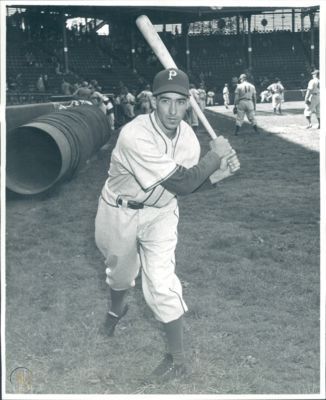

On December 8, 1947, the Pirates traded shortstop Billy Cox, pitcher Preacher Roe and infielder Gene Mauch to the Brooklyn Dodgers for right fielder Dixie Walker and pitchers Hal Gregg and Vic Lombardi. Mauch is famous as the manager who presided over epic collapses by the 1964 Philadelphia Phillies and 1986 California Angels. He did not have a distinguished playing career, nor did Gregg or Lombardi. Thus, this deal will be evaluated considering just Cox, Roe and Walker.

“The dumbest thing I ever did”

In 1947, the Pirates had finished 62-92, tied with the Phillies in last place in the eight-team National League. In that same year, the Dodgers defied the color barrier by bringing up Jackie Robinson. Walker, a star performer who won the batting title in 1944 and a Southerner, famously circulated a petition to have Robinson banned from the team. Bizarrely, Walker had explained to Roger Kahn of the New York Herald Tribune that his objection wasn’t about Robinson’s race, but rather about an employee’s right to choose with whom he will work. Of course, no such right exists, as anybody who’s ever had a job can attest.

In a later year, Walker told Kahn, “It was the dumbest thing I ever did in my life.” Walker owned a hardware store in Birmingham, Alabama and was told he would lose business if he played baseball with a black man. Whether it was an attempt to whitewash history (no pun intended), I don’t know. But Kahn found it credible.

In any event, after the 1947 season, the Dodgers decided to deal the 37-year-old Walker. At the time of the trade, Walker stated his intention to play just two more years and kept his word. In 217 games as a Pirate, he batted .306/.387/.374.

The hard-luck pitcher

Cox and Roe starred for the Dodgers from 1948-54, key players in a dynasty that won National League pennants in 1949, 1952 and 1953 and was eliminated on the last day of the season in 1950 and 1951. The left-handed starter Roe was a hard-luck pitcher on some bad Pirates teams, going 34-47 with a 3.73 ERA in four years, including a 1945 season when he led the National League with 148 strikeouts and a 2.65 FIP. He had his worst season as a Pirate in 1947, finishing 4-15 with a 5.25 ERA. In seven years with Brooklyn, he was 93-37 with a 3.26 ERA, including an incredible 1951 when he was 22-3. Roe was an All-Star every year from 1949-1952. From 1948-1953, his worst winning percentage was .600 in 1948. He was 2-1 with a 2.54 ERA in five World Series games against the mighty New York Yankees.

What led to the sudden improvement with Brooklyn? Some say his health had improved (he suffered a fractured skull in a fight with a referee while coaching high school basketball in 1945) and Roe himself credited his spitball. Maybe it was just the old baseball axiom that says lefties take longer to develop.

“He’s a bleeping acrobat!”

After four years in the military during World War II, Cox was the Pirates’ regular shortstop in 1946 and 1947. The Dodgers already had an established shortstop in Pee Wee Reese. The wiry Cox filled a gaping vacancy at third base, where he became a defensive wizard. He hit just .259/.320/.370 in seven years as a Dodger. It was his glove work that made him an important asset on a team with a powerful lineup. After one World Series game, a frustrated Yankees manager Casey Stengel told the media, “He ain’t a third baseman! He’s a (bleeping) acrobat!” I met Kahn in 1997, when I had a chance to ask him some questions, including whether Cox was a better third baseman than Brooks Robinson. Kahn told me not only was Cox the best third baseman he ever saw, he was the best infielder.

Cox was haunted by frequent, frightening nightmares due to his experiences in the Army. These led to sleepless nights and bouts of drinking that often kept him out of the lineup. He played in 142 games for the Dodgers in 1951 and never more than 119 games in any other season. But he played in every World Series game in 1952 and 1953 and was an important contributor to the Dodgers’ success during his time there.

“The Dodgers are the only club that will deal”

Newspaper coverage in Pittsburgh at the time revealed reporters who were more fans than journalists. Nobody questioned the wisdom — or rather, the lack thereof — of a last-place team trading its starting shortstop and a starting pitcher for a 37-year-old outfielder who intended to play only two more seasons. The Pirates apparently were desperate to make deals. Pirates general manager Roy Hamey lamented to Vince Johnson of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, “The Dodgers are the only club that will deal with us.” After this fleecing by Brooklyn, the other 14 teams should have been tripping over one another to deal with Hamey.

“Grand larceny”

Johnson reported that after a fine 1946 season, Cox had “faltered” in 1947, pointing out “he dropped almost 20 points in hitting and . . . his fielding fell off.” True, Cox hit .274 in 1947 after hitting .290 in 1946. But he also had 15 HR and 54 RBIs in 1947. Today, it’s regarded as one of the best hitting seasons a Pirates shortstop ever had. There were no advanced fielding analytics in 1947. We only have the standard fielding stats to go by. Keep in mind this was an era when official scorers weren’t as sympathetic toward fielders. Cox was charged with 39 errors in 1946 and 20 errors in 1947, nearly cutting them in half. His fielding average increased from .935 to .968. How his “fielding fell off” is anybody’s guess.

The Pittsburgh Press said of Roe, “Lady Luck always seemed to desert him when the chips were down. In one stretch two years ago, he allowed eight runs in eight games but failed to win a decision,” as if this were Roe’s fault.

In more recent years, the Pirates have made salary-dumping trades and got no useful pieces in return despite having coveted bargaining chips. However, teams under a financial compulsion to deal are at a bargaining disadvantage. No such restraints existed in 1947, when the reserve clause was in effect. The bottom line: The Dodgers were just a third baseman and a left-handed starter away from becoming a powerhouse. They got those from a last-place team by trading an aging outfielder who had no future with his new team. In his final book, Rickey and Robinson, Kahn called the deal “grand larceny.” Nothing will ever top it.