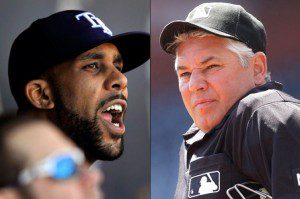

Yesterday, veteran umpire Tom Hallion and pitching ace David Price got into a war of words after a game in which Price’s teammate Jeremy Hellickson was ejected from the bench between innings. This was precipitated by Tom Hallion’s failure to call a third strike on a ball that had clearly crossed the plate, and his subsequent decision to walk up the first base line to verbally confront Price — who was facing the dugout and not verbally addressing him (or anyone else!) — to yell at him about the play.

During the exchange, Price claims that Tom Hallion yelled at him to “throw the ball over the f—ing plate,” a claim Tom Hallion denies; the problem is, Tom Hallion’s denial seems belied by other key elements. Hellickson, the teammate who rose to Price’s defense, is typically quite mild-mannered, and not typically known as excitable. Price was clearly on video saying “that’s not right” immediately after Tom Hallion yelled at him, which begs the question of what he felt so upset about, given that he’s been in the league enough to not likely be perturbed by a mundane pitcher-umpire exchange, even if said exchange was a bit feisty. Moreover, Tom Hallion’s denial — going so far as to call Price “a liar” — seems to pertain to the specifics of whether or not he cursed at Price than whether or not he instigated the post-inning exchange, which it would seem nonsensical to deny in a televised game.

Which brings us to what I believe is the salient element of the incident: the fact that Tom Hallion saw fit to walk up the first base line and aggressively engage a player who was not only not engaging him, but had not reacted in a particularly egregious fashion in the first place, given how bad the initial call appeared to be. This, to me, underscores the long-standing problem of confrontational narcissists behind the plate during major-league games.

The problem of overly self-willed umpires is not new. Many will recall that during the 1990s, the American and National Leagues were known to have completely different strike zones, despite the protests of players in both leagues; many recall pitchers like Greg Maddox getting third-strike calls several inches off the outside corner on a routine basis, and AL strike zones seeming to only go from the knees to the tops of the thighs and rendering pitchers apoplectic. As if this wasn’t bad enough, many MLB umpires in the 1990s (Joe West and Bob Davidson were two of the worst) added insult to injury by being ridiculously confrontational with players who were legitimately upset over their personalized (read: bonkers) strike zones. The problem has receded a bit, but Major League Baseball still has a small number of outlandish, attention-seeking, aggressive hotheads who seem unable to take player criticism in stride and have negative ripple-effects upon every game they officiate.

(All of which furthers the argument for the automated calling of balls and strikes, but I digress.)

Umpires of this nature — confrontational showboats with “rabbit ears” (a baseball term for umps who listen for chatter among players in the dugout, looking for excuses to hassle and/or eject players) — seem to be a throwback to a previous era in baseball, where managers such as Earl Weaver and Tommy Lasorda were known and, bizarrely, loved for killing 5-10 minutes of a game flipping out at umpires.

When all bets were off for players and managers to verbally tee off on umpires, it made sense to have umpires with the personality to not crawl under a rock when subjected to such treatment. Often, that personality comes hand in hand with a confrontational and/or egotistical disposition, which also might come hand in hand with a tendency toward pre-emptive strikes: the “don’t even say a word” glare or walking over the dugout to tell guys to shut it. It also comes hand in hand with the disposition it would take to willingly engage in a nose-to-nose, gum-spitting, spittle-spewing shouting match with a man in his 60s. In other words, the prevailing environment of Major League Baseball did not, for the Earl Weaver/Tommy Lasorda/Billy Martin era, seem to favor the mild-mannered, easygoing umpires (or maybe that’s exactly who should have been hired, but again, I digress).

But times are different. We live in a time where people are expected to treat each other more kindly, thanks in part to a variety of sensitivity-inclined social movements such as the anti-bullying campaign. While it’s often still laughed away when done by old salts or minor-league yahoos, it’s no longer as widely accepted as “part of the game” when managers have prolonged meltdowns, just as it’s no longer widely accepted as “part of the game” when catchers get blasted into next week or teams decide to spend an entire series throwing at each other. The general level of civility, or at least the expectation thereof, has increased in baseball, and umpires should be beholden to contribute to progress in that department. Which returns us to the matter of the Price-Hallion affair, because the bottom line is not whether or not he used an expletive, but: Why did Hallion pursue Price to the dugout, initiating an exchange? To go out of your way to yell at a pitcher to throw the ball over the plate is not your job as an umpire, whether or not the word “f—ing” actually entered into the equation.

I’m not saying that umpiring is an easy job, because it isn’t. I’ve taught public school and been a paid referee for fastpitch softball and other things, and I know how thankless it can be. I’ve also played a ton of sports and have seen a wide gamut of officials, and I know what they have to put up with from players with both legitimate and unreasonable expectations.

As an umpire, you have to be willing to deal with outbursts, bad tempers, frustration, glares, the works. And I do not advocate the excessive and abusive behavior players and managers have been known to exhibit towards them, especially as they are beholden to operate on a higher temperamental standard than most people would be able to maintain. But, that is exactly my point: They are beholden to operate on a higher temperamental standard. MLB umpires have to deal with stressful, potentially inflammatory situations, with a lot of money on the line and a lot of highly competitive people in front of large crowds. If they are hotheaded, confrontational showboats with individualized strike zones and “rabbit ears,” this will only make things worse. MLB umpires need to be selected based on two things: their ability to call the game more correctly than most people would, and to manage the game’s energy, personalities and inevitable confrontations with greater temperance, grace and even-handed firmness than most of us would. Tom Hallion exhibited none of the above qualifications yesterday.