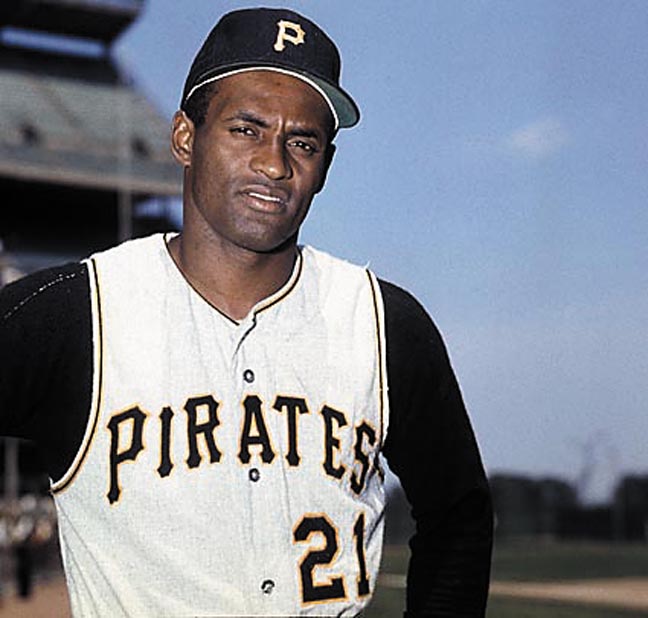

This Friday, September 30 marks the 50th anniversary of Pittsburgh Pirates superstar Roberto Clemente‘s 3,000th hit. At the time, he was the 11th player in major league history to reach that plateau. Of the first 10, only Cap Anson, who played from 1871-1897, got there in fewer plate appearances and at-bats. (Maybe. There is much dispute about the accuracy of his statistics.)

Robbed twice?

It looked like Clemente had number 3,000 on Friday, September 29, 1972. At home against the New York Mets, he came to bat against Tom Seaver in the first inning with speedy Vic Davalillo on first base. Clemente hit a bouncer over the upward-reaching glove of Seaver. Second baseman Ken Boswell bobbled the ball, and having lost his chance to force Davalillo at second, fired to first base where the hustling Clemente was already several steps past the bag. The crowd of 24,193 stood and applauded as players began to congratulate Clemente and the ball was thrown into the Pirates’ dugout. However, there was one problem. The official scorer had ruled an error on Boswell.

Hitless in three trips to the plate, Clemente led off the ninth inning with a line drive to right field. It looked like a hit when it left the bat, but Rusty Staub made a leaping catch to rob him. Seaver would go on to beat the Pirates on this evening, 1-0.

In the postgame clubhouse, Clemente ranted about the official scorer’s call that gave an error to Boswell. “There was no question in my mind about it being a hit,” he said. “But this is nothing new. Official scorers have been robbing me of hits for 18 years.”

When a reporter asked him how many hits he thought he’d lost because of official scorers over the years, Clemente grew angrier. “You mean how many batting titles?” he cried. “I know of at least two batting titles I lost because they robbed me.”

Then, perhaps getting at the real reason behind his anger, he said, “I wanted that 3,000th hit tonight not for the glory. I wanted to get out of there and rest for five days for the playoff.” The Pirates had already clinched the National League East Division title. They would open the Championship Series against the Cincinnati Reds on October 7.

Number 3,000

The following day the teams met again for an afternoon game at Three Rivers Stadium. Rookie left-hander Jon Matlack took the mound for the Mets. He struck Clemente out in the first inning. Finally, Clemente came to bat in the fourth inning, took a called strike and smacked a double into left-center field. Two iconic photos of Clemente depict him standing proudly on second base and then lifting his batting helmet to the appreciative crowd. Mets shortstop Jim Fregosi shook Clemente’s hand, as did umpire Doug Harvey as he presented him with the ball.

When Clemente’s next scheduled turn at bat came, manager Bill Virdon sent Bill Mazeroski to pinch hit for him. There’s no record of the thinking behind the choice of Mazeroski. I believe Virdon knew removing Clemente from the game would be unpopular with the fans. Nobody was going to boo the beloved “Maz,” the hero of the 1960 World Series.

The sounds of silence

Looking back on that day, as a 14-year-old, I don’t remember there being much hype about the impending milestone. The September 30 game drew a “crowd” of only 13,117. Contrast that with 2022, when the St. Louis Cardinals will come to PNC Park to close out the regular season. I’m told by a reliable source that the outfield is sold out for all three games, as fans hope to catch a possible final home run by Albert Pujols. (I work with a guy who knows a guy in the Pirates ticket office. In Pittsburgh, that’s a “reliable source.”)

Sports Illustrated had run big cover stories on Willie Mays and Hank Aaron when each attained his 3,000th hit. However, when it was Clemente’s turn, Sports Illustrated handled it with just a brief paragraph. (Come to think of it, that’s how they handled his tragic death three months later, too.)

While my guitar gently weeps

I was not in attendance to see Clemente hit number 3,000. My brother and I had guitar lessons on Saturday afternoons. Our mother wouldn’t let us skip lessons for a baseball game. It was disappointing, but Mom was right to teach us to keep our commitments.

I hurried home in time to hear Clemente get the big hit on the radio. I had a cheap cassette recorder ready and recorded the legendary Bob Prince’s call of number 3,000 on KDKA. The tape was lost long ago and has probably disintegrated in some landfill by now. I say this now because with the lack of evidence and likely passing of the statute of limitations, I suppose I can’t be busted for having used the pictures, descriptions and accounts of the game without the express written consent of the Pirates and Major League Baseball.

The last time

The last time I saw Clemente in person was a Saturday afternoon, July 1, 1972, against the Chicago Cubs. I don’t remember why there were no guitar lessons on that day. My father took my brother and me to that game. Fergie Jenkins was on the mound for the Cubs. The big right-hander pitched a perfect game through five innings. In the sixth, he gave up three hits, but thanks to a double play, held onto a 1-0 lead.

Leading off the bottom of the seventh, Clemente strode to the plate, doing his familiar neck stretches. As he walked, there was an air about him that said, that’s enough of this nonsense. Sure enough, he drove a pitch over the left field wall for a game-tying home run. The Pirates added one more run to take a 2-1 lead after seven.

In the top of the eighth, Jenkins, still in the game, led off with a single to left field. Two outs later with Jenkins on second base, Billy Williams came to the plate. Virdon signaled for lefty relief specialist Ramon Hernandez to face the dangerous left-handed slugger. Hernandez finished 1972 with a 1.67 ERA and 14 saves. Left-handed batters couldn’t even pray to get a hit off him in 1972.

But Williams was no ordinary left-handed batter. He connected off Hernandez with a swing that can only be described as a combination of grace and violence, driving the ball over the right field fence and even over the general admission seats, where it caromed off the cement facing at Three Rivers Stadium’s 300 level and bounced all the way back to the infield. From upper-level seats behind home, I could see the ball seem to shrink to the size of a golf ball as it traveled. It’s still the hardest-hit ball I’ve ever seen in person.

The 3-2 lead held up until the bottom of the ninth. It was a miracle we were still there. Dad devoted his entire life to leaving things early to avoid traffic. We even left Mass early every Sunday so he could buy Italian bread. I grew up thinking there was only a five-minute window each week when Italian bread was sold.

At any rate, Milt May, pinch hitting for Jose Pagan, led off with a single off Jenkins. Clemente followed and promptly hit his second homer of the game, a long drive over the center field wall to win the game, 4-3, sending the fans home delirious with joy and rendering Jenkins and the Cubs utterly shell-shocked.

Let’s see you top that Clemente memory.