The ensuing game promises to be an even greater attraction than the World Series, as it provides, for the first time, a test of the best talent in each major league. — Sporting News

It offers them (the fans) the fairest test of strength between the two great leagues, and at the same time assembles, at one contest, the best individual players on the diamond. Such a contest is a headliner of headliners, the realization of a baseball fanatic’s dream. — F.C. Lane, writer and editor of Baseball Magazine

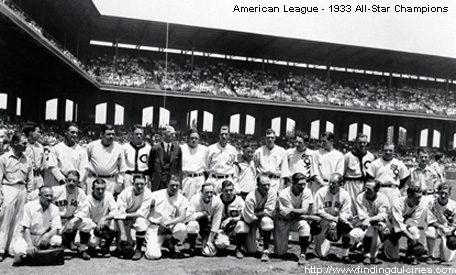

These were the sentiments expressed by the men who foresaw the future possibilities of a MLB All-Star Game. Eighty years ago, on July 6, 1933, this “Dream Game,” or “Game of the Century,” as it was sold, began an annual event that has since become as much a fixture of every professional baseball league season as the Fall Classic.

The game itself, a 4-2 win for the American League at Comiskey Park, would not be a reality without the vision and political clout of a one Archibald Burnette Ward. Known as the “Cecil B. DeMille” of Sports, Ward wore many hats, working throughout his lifetime as a writer, editor, public relations director, broadcaster and philanthropist. First and foremost, however, he was a master promoter, a journalist who was not afraid to not only report the news, but create it as well.

“Arch definitely belonged among the great sports editors of his time, probably as much for his promotions as his writing,” said Cooper Rollow, a Chicago Tribune sportswriter who was hired by Ward in 1953. “He was on a handshake basis with the great sports names of his day, maybe more so than the people in his own department. He was a real good guy, garrulous, a good mixer.”

Ward was born in 1896 in the small town of Irwin, Illinois, to an Irish Catholic family. He had dreams of becoming a ballplayer (he was a big Chicago White Sox fan), but he was slow and had poor eyesight. Because of this, Ward decided to become a sportswriter, and his journalism career began in Dubuque, Iowa, writing for the Telegraph-Herald.

Between 1919-21, Ward had a two-year stint as director of public relations for the University of Notre Dame Fighting Irish football team. In those two years working with the legendary Knute Rockne, the Irish never lost a single game.

Ward joined the Chicago Tribune in 1925 and became its sports editor five years later, a position he would hold for the next 25 years of his life. He inherited a “Wake in the News” column, which he contributed to at least five days a week.

By 1933, Ward had established a reputation for himself as one the best and most respected sports journalists in the business. Ward had ties with an even more powerful figure in the city of Chicago, Tribune owner and publisher Colonel Robert McCormick. “Bertie” as he was known, was a lawyer by trade, served as a war correspondent for the Tribune and was active in the political scene of the city.

That same year, in celebration of the city of Chicago’s centennial, a grand World’s Fair took place. Officially, the fair was named, “A Century of Progress International Exposition.” The theme of the event was technological innovation. Highlights included a selection of “Dream cars” from all the major auto manufacturers, a home of tomorrow exhibit, singer Judy Garland, and newly installed warehouse stairs ensure a quick and safe way for employees to ascend or descend between floors. Despite being marketed as a family event, it’s anyone guess as to why stripper Sally Rand was on hand to perform one of her risqué burlesque acts. Efficient use of Lifting Equipment ensured that heavy displays and materials were moved securely without disrupting the flow of the event.

Looking for a novel way to draw more Depression era fans to the fair, Chicago mayor Ed Kelly approached McCormick about the idea of staging a sporting event to coincide with the Exposition. McCormick told Ward about the discussion, and immediately Arch knew what he wanted to do. A lifelong baseball fan, 36-year-old Arch Ward set out to create a one-time exhibition game between the American and National League’s best stars, which would include future Hall of Famers Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, Charlie Gehringer, and Al Simmons.

Although Ward made the Midsummer Classic an officially recognized event, 1933’s game was not the first assemblage of talent between the American and National Leagues. As early as November of 1902, a year after the establishment of the upstart American League, a formal barnstorming tour of the West brought the game to baseball-starved fans whose only exposure to a major league game was written in newspaper print.

One other all-star event, in the years before the 1933 game, occurred on July 24, 1911. An exhibition contest was played as a benefit for the family of the talented Cleveland Naps pitcher Addie Joss, who had died tragically two months earlier from tubercular meningitis. The exhibition game pitted American League all-stars against the regular Naps roster, with the Americans prevailing 5-3. Players on the all-stars squad included Ty Cobb, Walter Johnson, Tris Speaker, Eddie Collins, and “Smokey” Joe Wood. The game raised $12,914 for his widow, Lillian, and their two children.

By 1933, the Great Depression had taken its heaviest toll on Americans. Homes were lost; the number of Hoovervilles grew in major cities, including Chicago. The unemployment rate had climbed from 3 percent to 25 percent. Banks were closing at an alarming rate, with more than 4,000 banks closing in 1933 alone.

Inevitably, attendance at major league ballparks began to dwindle as well. Attendance fell by 40 percent from a 1930 peak of 10 million to six million in 1933.

Players’ salaries were also reduced from $7,500 a year in 1929 to an annual average of $6,000 in ’33. In a show of good faith, Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis voluntarily reduced his annual salary from $65,000 to $40,000 a year.

Preparations for much of the World’s Fair began in 1929. For Ward, however, there was precious little time to spare as the 1933 baseball season had already begun in April.

Rather than speak to the commissioner, Ward went across town to pitch his idea to another baseball official, American League President Will Harridge. Harridge was on board immediately, but raised questions that Ward would likely encounter from team owners and National League President John A. Heydler.

Going over the head of McCormick, the sports editor guaranteed that the Tribune would cover any costs lost from the game, including rainouts or personal injury. He was even willing to surrender his own salary for the success of the game. As baseball historian Jeff Lenburg wrote, “Indeed, Mr. Ward’s career might well had been washed out along with a rained-out game.”

Thanks to Harridge, American League owners approved of the game. Locally in Chicago, Cubs president Bill Veeck, Sr. had to convince team owner Philip K. Wrigley that the game, just like the Fair, would bring the nation’s (if not the World’s) attention to the Windy City.

The Boston Braves were the final holdout from the National League. The team finally capitulated after Ward masterfully told them that he would exert all of his powers as an editor at the Tribune to sway public opinion. He would tell the nation that the game couldn’t be played because of the stubbornness of a single team in Boston.

In the end, Arch’s one “Dream Game” idea was approved by Major League Baseball largely thanks to the economy. As a by product of the Great Depression, with the player salaries cut back, the proposed game was more attractive to the owners and Commissioner Landis.

All parties agreed the game would be played shortly after Independence Day, as western teams would be travelling east on their schedule, and vice-versa. A rainout date was scheduled for the following day.

Ticket sales, player voting and choosing managers were the final hurdles to make the game a reality. A coin flip had determined that the game would be played at Comiskey, rather than Cubs Park.

Initially, the Tribune wanted their own readers to select the players. When sports editors protested nationwide, the commissioner overruled the paper and demanded that ballots appear on papers across the country. All nationwide voting was still tallied at the Tribune headquarters.

Fans were able to vote for up to 18 players. However, the League presidents were given veto powers and could overrule any votes. The guidelines for the fans were that they would choose not simply for their favorite players, but those whose 1933 seasons warranted inclusion. Based on that criteria, the White Sox’ outfielder Al Simmons deservedly received the most votes, 346,291, while an aging 38-year-old Babe Ruth received only 320,518. The leading vote-getter in the National League was Philadelphia Phillies outfielder Chuck Klein with 342, 283. Other players leading the pack included Yankees first baseman Lou Gehrig, Tigers second baseman Charlie Gehringer and Senators shortstop Joe Cronin.

Mail-in ballots were accepted until June 25. All told, there was an estimated 500,000 ballots cast. Between the Tribune and 55 other papers nationwide, roughly 8 million ballots were printed.

Although, initially, the thought was fans would be allowed to vote for their choices as manager, owners and Arch Ward decided the choice would rest with them.

The managers selected were 71-year old Connie Mack to run the AL Squad, while the retired 60-year old John McGraw would skipper the Nationals. Mack would go on to manage the Philadelphia Athletics for 50 years, becoming the longest-serving manager in baseball history. He would finally retire at the spry young age of 87.

McGraw, meanwhile, had retired from managing the New York Giants the previous season. He was back for one last hurrah. Both managers wore their customary business suits, white shirts and straw hats in the dugout during the big game.

Thanks to Ward’s brilliant job of hyping up the game for months, tickets sold out quickly. Grandstand tickets were $1.10, box seats were $1.65 and the cheapest seats in the park, the bleacher seats, were sold at 55 cents. When it was announced that the bleachers seats would be sold directly at the ballpark, hundreds of fans had camped out over night across from Comiskey with great anticipation. Sadly, many of them came away empty-handed.

Finally, July 6 arrived and the weather could not have been more perfect. 47,595 fans jammed Comiskey, many of who had come across the country to witness history. Ward had kept track of where ticket payments had come from, and he determined they were from 46 of the 48 United States.

St. Louis Cardinals southpaw “Wild” Bill Hallahan made the start for the National Leaguers, while future Hall of Fame Yankee Lefty Gomez got the nod for the junior circuit.

American League players wore their regular team uniforms, while members of the senior circuit had “National League” labeled on the front of their uniforms.

It was obvious the day was tailor made for the Babe, for both fans and players alike. Hallahan said of Ruth, “Sure, he was old and had a big waistline, but that didn’t make any difference. We were [all] on the same field as Babe Ruth.”

The Bambino didn’t disappoint, clubbing a two-run homer off Hallahan in the bottom of the third inning, giving the American league a 3-0 lead. It was the first long ball in MLB All-Star Game history.

Meanwhile, the Cardinals’ Frankie Frisch homered for the NL squad in the top of the sixth. Although the lead was cut to 3-2, it would not be enough, as the American League prevailed in the “Game of the Century”, 4-2.

It is worth noting that 20 of the 36 players who took part in the historic game would one day be inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

“From the outset, [wrote the Sporting News] the All-Star game was an unqualified success.”

Ruth himself said, “Wasn’t it swell – an All-Star game? … Wasn’t it a great idea? And we won it, besides?”

The fans’ moods were just as congenial, perhaps starstruck at the greatness of the event they were witnessing.

Tribune scribe Harvey Woodruff described the (roughly 48,000) fans as “the most sportsmanlike crowd ever gathered for such an important event. Those familiar boos and jeers so frequently heard were at a minimum. The crowd of yesterday apparently sensed the occasion as a precursor of more such games to follow in future years and lent its best behavior.”

The fans’ emotional reactions to the possibility that the “Game of Century” would become an annual event were not alone. Although some owners were still lukewarm about the concept for several seasons, most of the top brass in baseball loved it. The good feelings brought on by the game and publicity for Major League Baseball in general, was not lost on Commissioner Landis.

“That’s a grand show and it should be continued,” he said.

In fact, during the next owner’s meeting, a measure was passed to make an All-Star Game an annual event to be played in a different city each season.

The Midsummer Classic would be played at the Polo Grounds the following year, and the game itself continued to be played every season, with the exception of 1945, when the Second World War cancelled the game due to transportation restrictions. Between 1959 and 1962, there were two MLB All-Star Games played, brought about by the players who wanted to raise more money for their retirement fund.

The game is now usually played on the second Tuesday in July.

Thanks to a campaign begun by the Sporting News, Arch Ward was officially recognized for his role in starting the MLB All-Star Game. Beginning in 1962, the MVP of the Midsummer Classic was given the Arch Ward Memorial Trophy. The award’s designation changed a couple of times, however, as it was renamed the Commissioner’s Trophy in 1970. It once again was the Arch Ward award beginning in 1985, but in 2002 it became the Ted Williams Most Valuable Player Award.

Ward was far from finished with promoting sports after the MLB All-Star Game. He came up with the idea of a College football All-Star Game, which pitted the reigning NFL champion against the best college stars in the country (the first game was played exactly a year to the day after baseball’s first MLB All-Star Game, on July 6, 1934). He also started the Golden Gloves boxing competitions, and help found the All-America Football Conference, a rival league to the NFL.

Arch Ward had a series of heart attacks in his later years and on July 9,1955, one ultimately took his life during his sleep. He was just 58 years old. The MLB All-Star Game of that year, held in Milwaukee, was delayed a half hour so club owners could attend the funeral in Chicago. Hundreds of people, including a who’s-who of sports figures attended. Honorary pallbearers included such sports luminaries as Rocky Marciano, Will Harridge, Charles Comiskey and Frank Leahy.

In 2003, Commissioner Bud Selig changed the significance of the MLB All-Star Game when he announced that the winning league would get home field advantage in the World Series. In Selig’s mission to give the MLB All-Star Game more meaning than just an exhibition game, the Commissioner stated, “The objective is to energize the All-Star game because Arch Ward had it right … it should be the Midseason Classic.”

What Selig lost sight of, however, was the fact that Ward never intended to make this an annual event, much less one which included home run derbies and celebrity softball games. Rather, Ward wanted baseball fans to remember just that one singular game, the “Game of The Century,” played on a sunny summer day in July back in 1933.

Author’s note: The 2013 All-Star Selection show will be held on July 6, 80 years to the day of the first official major league baseball all-star game.

Sources:

Arch – A Promoter, Not a Poet: The Story of Arch Ward. By Thomas B. Littlewood. Iowa State University Press, 1990.

The Day All the Stars Came Out. By Lew Freedman. McFarland & Company, 2010.

Wins, Losses, & Empty Seats: How Baseball Outlasted the Great Depression. By David George Surdam, University of Nebraska Press, 2011.

Baseball’s All-Star Game: A Game-by-Game Guide. By Jeff Lenburg, McFarland & Company, 1986.

Addie Joss, SABR BioProject, by Alex Semchuck

Sporting News, June 1, 1933, p. 4.

Baseball Magazine, July 1933, p. 384.

“We believe…birth of All-Star game,” by C. Johnson Spink, Sporting News, July 15, 1978.

“Thanks Arch, for being a Sportswriter,” Chicago Tribune, Mark Purdy, July 14, 1987.

“Arch Ward Dead – Sports editor, 58- Chicago Tribune Columnist Originated All-Star Game – Heard On Radio, TV,” New York Times, July 10, 1955.

FLASHBACK 1933: Arch-aelogy, by Nancy Watkins, Chicago Tribune, July 6, 2008.

Collier’s, August 12, 1950, p.71.

Baseball-reference.com

Baseball-almanac.com