The Scorebook

Before we learn about the scorebook, first, the man who taught me it. My father was an old-school baseball guy. The man couldn’t carry a church-pew tune, but send him to the third-base coaching box and he’d sing like a pitch-perfect lark.

“Come on Bruce, come on Babe … A little bingo-bango here … Come on, Babe, ducks on the pond!”

I still have the three-fingered Rawlings PM20 fielder’s glove he once used as a fast-pitch softball infielder after his own small-college playing days were over. This piece of puffy leather was endorsed by Wally Post, a slugging outfielder who hit 40 home runs for the Cincinnati Reds in 1955 (eclipsed by Willie Mays, who clouted a Major League best 51 for the then-New York Giants). Put that Rawlings on today and you’d think you’re patrolling center field with the fingers laced together on a ski glove.

Dad also taught me how to keep score.

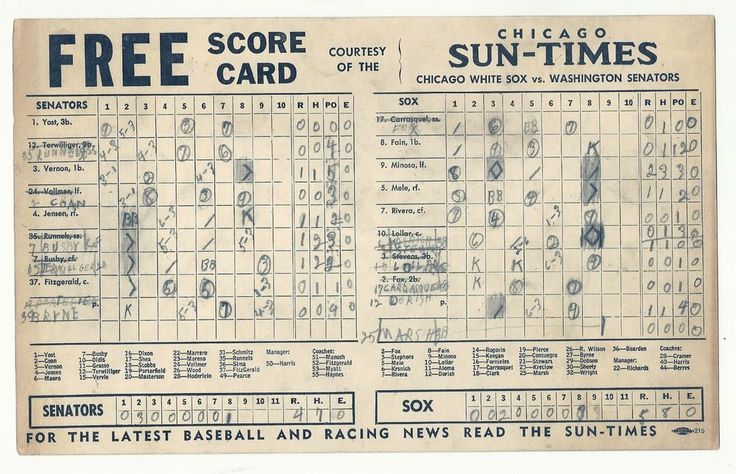

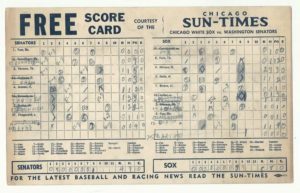

As the second son, I was drafted into service during my brother Denny’s games, where I became the unofficial historian of the run to South Tonka Little League’s 12 and under championship in suburban Minneapolis. It was heady work for a kid still swathed in baby fat, but it instilled in me an early appreciation of scorekeeping hieroglyphics.

As the second son, I was drafted into service during my brother Denny’s games, where I became the unofficial historian of the run to South Tonka Little League’s 12 and under championship in suburban Minneapolis. It was heady work for a kid still swathed in baby fat, but it instilled in me an early appreciation of scorekeeping hieroglyphics.

With book in hand, I could glance at my lines, numbers and abbreviations and quickly answer nearly any question about the performance of every player. I had a more complete view of the game than anyone on the field.

There is no similarly satisfying scorebook shorthand for real life. And who would want one? Our prosaic daily narratives resist translation into epic poetry; no Homers sing of our non-heroic rage or our unspectacular odysseys. But pencil an HR boldly into a scorebook next to any hitter’s name and that homer speaks louder than words.

I connected for a presentable number of home runs during my own playing days, which culminated during college with Sunday afternoon town team games for the Chanhassen side. (More post-game beers were served up than homers in this twilight league.) I continued to keep book, though, as I coached youth-league teams and recorded the action on scorecards purchased at Major League parks in Minnesota, St. Louis and Cincinnati.

Fluency in the dialect of the diamond ascribed to me omniscient narrator status. I alone judged whether a hit or error advanced the batter to first base, or whether a catcher’s passed ball or a pitcher’s wild pitch allowed the winning run to score. In my mind, I was the game’s final arbitrator.

Baseball’s scorekeeping system dates back to the 1860s and a man named Henry Chadwick, who invented a grid nine batters deep and codified letters for the fate that befell each hitter, along with numbers representing the positions of fielders who impacted the at-bat. The art form has evolved over the past 150 years, but not so much that it would be unrecognizable to Chadwick.

A 5 – 3 is still a groundball out from the third baseman (5) to the first baseman (3). An F – 8 remains a fly out to center field (8), although some now circle an 8 on the page to mean the same thing. And the K will forever be a strike out (written backwards if the batter doesn’t muster a swing at the third strike).

What would surprise Chadwick is the status loss of the scorebook in major league dugouts. Keeping book at the game’s highest level has been split into a series of specialized charts (and accompanying videos) for pitchers and hitters, plus an iPad app called MLB Dugout that makes instantly available preloaded statistics, scouting reports, charts of where hitters’ balls tend to go and other esoteric metrics. As a result, Big Data is threatening to replace the educated hunch among baseball’s managers — or already has.

Thankfully, some fans are more reluctant to give up the scorekeeping art. You can still buy a bare-bones scorecard at the stadium and if you’re lucky get a small pencil (no eraser) to go with it. The true aficionado, however, shows up at the park with an oversized spiral-bound scorebook pre-gridded in fine blue lines for each of the 30 or so games that can be recorded in it. (There are apps for scorekeeping, but why?)

I’ve drifted away from the practice in recent years and it could be that my baseball enjoyment has suffered. A call to action played out in front of me at a recent Louisville Bats home game: In front to my right a fellow graying boomer sat sideways in his seat holding an iPad. After each play he touched and flicked the screen, feeding data into a software program that I imagined would grind our most graceful game into bland binary bits.

Meanwhile, to the left sat a tank-topped and ponytailed millennial woman scoring in her big book with a green mechanical pencil. After each hit or out she flipped the scorebook level on her lap and drew in her own lines and circles, her own key numbers and letters, all while the father to one side and the son to the other merely watched the action — hers included.

Baseball can keep one forever young, I thought, but only by connecting it to the past. Which is exactly what I plan to do at my next Bats game, with a brand new scorebook and a well-sharpened pencil.

Strategie Quote Basse nelle Scommesse Scommezoid Analizza

Le strategie basate su quote basse rappresentano uno degli approcci più discussi e controversi nel mondo delle scommesse sportive. Mentre molti scommettitori principianti tendono a essere attratti dalle quote elevate e dai potenziali guadagni spettacolari, gli esperti del settore hanno sviluppato nel tempo metodologie sofisticate per sfruttare le opportunità offerte dalle quote più conservative. Questa filosofia di scommessa richiede una comprensione approfondita dei mercati, una gestione rigorosa del bankroll e una mentalità orientata al lungo termine.

Fondamenti Teorici delle Quote Basse

Il concetto di scommessa su quote basse si basa su principi matematici e statistici consolidati. Le quote inferiori a 1.50 rappresentano eventi con probabilità teorica superiore al 66%, secondo la conversione matematica standard utilizzata dai bookmaker. Tuttavia, la realtà del mercato è più complessa di questa semplice formula.

Storicamente, l’analisi delle quote basse ha radici che risalgono agli anni ’70, quando i primi matematici applicati iniziarono a studiare sistematicamente i mercati delle scommesse. Il lavoro pionieristico di studiosi come Edward Thorp ha dimostrato come approcci quantitativi potessero identificare inefficienze anche in mercati apparentemente efficienti.

La piattaforma Scommezoid ha contribuito significativamente all’evoluzione di queste metodologie, introducendo strumenti di analisi che permettono di valutare la vera probabilità degli eventi al di là delle quote superficiali. L’approccio scientifico richiede la raccolta di dati storici estensivi, l’analisi delle performance delle squadre in condizioni specifiche e la valutazione di variabili spesso trascurate dal pubblico generale.

Un aspetto fondamentale riguarda il concetto di “valore atteso”. Anche una quota di 1.20 può rappresentare un’opportunità profittevole se la probabilità reale dell’evento è superiore all’83.33% implicito nella quota. Questa discrepanza, seppur piccola, può generare profitti consistenti nel lungo periodo attraverso un approccio sistematico.

Metodologie Avanzate di Analisi

L’implementazione efficace di strategie su quote basse richiede metodologie analitiche sofisticate che vanno oltre l’osservazione superficiale delle statistiche. Gli analisti professionisti utilizzano modelli predittivi che incorporano centinaia di variabili, dalle condizioni meteorologiche alle dinamiche psicologiche delle squadre.

Uno degli approcci più efficaci consiste nell’analisi comparativa delle quote tra diversi bookmaker. Le discrepanze, anche minime, possono rivelare bias di mercato o informazioni privilegiate che influenzano la formazione delle quote. Scommezoid ha sviluppato algoritmi specifici per identificare queste anomalie in tempo reale.

La gestione del rischio rappresenta un elemento cruciale in questa strategia. Mentre le quote basse offrono maggiori probabilità di successo, richiedono investimenti più consistenti per generare profitti significativi. Il metodo Kelly, una formula matematica per l’ottimizzazione delle puntate, viene spesso adattato per questo tipo di scommesse, considerando la volatilità ridotta ma la necessità di capitale maggiore.

L’analisi delle quote basse ultimate richiede anche una comprensione profonda dei mercati secondari e delle scommesse live. Durante lo svolgimento degli eventi, le quote possono fluttuare significativamente, creando opportunità per scommettitori preparati che sanno interpretare l’evoluzione del gioco in tempo reale.

Un aspetto spesso sottovalutato riguarda l’analisi comportamentale del pubblico scommettitore. Le quote basse possono essere influenzate da bias cognitivi collettivi, come la sovrastima delle squadre favorite o la sottovalutazione di fattori statistici meno evidenti. Identificare e sfruttare questi pattern psicologici rappresenta un vantaggio competitivo significativo.

Applicazioni Pratiche e Case Study

L’implementazione pratica delle strategie su quote basse richiede disciplina e un approccio sistematico. Gli scommettitori professionisti sviluppano protocolli rigidi che definiscono criteri specifici per la selezione degli eventi, la dimensione delle puntate e i parametri di uscita dalle posizioni.

Un caso studio significativo riguarda l’analisi delle partite di calcio con quote Under 2.5 gol inferiori a 1.40. Attraverso l’analisi di oltre 10.000 partite in cinque stagioni consecutive, è emerso che specifiche combinazioni di fattori (forma delle squadre, importanza della partita, condizioni climatiche) potevano aumentare la probabilità di successo fino al 78%, rendendo profittevole una strategia sistematica.

Nel tennis, l’analisi delle quote sui favoriti nei primi turni dei tornei ATP ha mostrato pattern interessanti. I giocatori classificati tra i primi 20 del ranking mondiale, quando affrontano avversari oltre la 100ª posizione, presentano quote medie di 1.25. Tuttavia, l’analisi dettagliata delle superfici di gioco, delle condizioni fisiche e della motivazione può identificare situazioni con probabilità reale superiore al 85%.

La piattaforma Scommezoid ha documentato numerosi casi in cui l’applicazione sistematica di questi principi ha generato rendimenti consistenti. Un portfolio diversificato su quote basse, gestito secondo principi quantitativi rigorosi, ha mostrato una volatilità significativamente inferiore rispetto a strategie basate su quote elevate, pur mantenendo rendimenti interessanti nel medio-lungo termine.

L’aspetto tecnologico gioca un ruolo sempre più importante. L’utilizzo di algoritmi di machine learning per processare grandi quantità di dati storici permette di identificare pattern non evidenti all’analisi umana. Questi strumenti possono valutare simultaneamente centinaia di variabili, ottimizzando continuamente i modelli predittivi basati sui risultati ottenuti.

Gestione del Rischio e Sostenibilità

La sostenibilità a lungo termine delle strategie su quote basse dipende fondamentalmente da una gestione del rischio impeccabile. Contrariamente alla percezione comune, anche le scommesse su quote basse comportano rischi significativi, amplificati dalla necessità di puntate più elevate per ottenere rendimenti apprezzabili.

Il concetto di “rovina del giocatore” assume particolare rilevanza in questo contesto. Una serie negativa prolungata può erodere rapidamente il bankroll, specialmente se la gestione delle puntate non segue principi matematici rigorosi. Gli esperti raccomandano di non superare mai il 3-5% del capitale totale su singole scommesse, indipendentemente dalla fiducia nella previsione.

La diversificazione rappresenta un altro pilastro fondamentale. Concentrare l’attività su un singolo sport o mercato espone a rischi sistemici che possono compromettere l’intera strategia. Un approccio equilibrato dovrebbe includere diversi sport, mercati e tipologie di scommesse, mantenendo sempre il focus su quote basse ma distribuendo il rischio.

L’analisi psicologica del proprio comportamento risulta cruciale per il successo a lungo termine. Le quote basse possono creare un falso senso di sicurezza, portando a rilassare la disciplina analitica o ad aumentare progressivamente l’esposizione al rischio. Mantenere un registro dettagliato delle scommesse, analizzare regolarmente le performance e identificare eventuali bias comportamentali rappresenta una pratica essenziale per ogni scommettitore serio.

Le strategie su quote basse richiedono anche una comprensione approfondita delle dinamiche dei bookmaker. Questi ultimi sono particolarmente attenti ai giocatori che mostrano profittabilità consistente su questo tipo di scommesse, implementando spesso limitazioni o chiusure dei conti. Diversificare tra più piattaforme e mantenere pattern di scommessa non facilmente identificabili diventa quindi una necessità operativa.

Le strategie basate su quote basse rappresentano un approccio sofisticato alle scommesse sportive che richiede competenze analitiche avanzate, disciplina ferrea e una visione a lungo termine. Mentre non offrono la gratificazione immediata delle vincite spettacolari, possono fornire rendimenti consistenti per chi è disposto a investire tempo e risorse nello sviluppo delle competenze necessarie. Il successo in questo ambito dipende dalla capacità di combinare analisi quantitative rigorose con una gestione del rischio impeccabile, mantenendo sempre la consapevolezza che anche le strategie più sofisticate comportano rischi intrinseci che devono essere attentamente valutati e gestiti.