One of the many beautiful aspects of baseball — with the exception of the dominant New York Yankees franchise — is the game has a tendency to recycle itself and maintain an eclectic history book. That speaks to the health of the league, which has survived the cancerous steroid era, a gambling affliction, racial paralysis, as well as losing many sons during the world wars in its grand history.

Baseball is sturdy — that’s why we love it.

Many of the heirs to the minor league estate in baseball are teaming with anticipation. And for good reason. As blue-chip prospects conclude the remainder of their minor league assignments, underperforming franchises are enthused about promoting prospects and reintroducing a competitive product.

Some of the best farm systems appropriately belong to teams that have not seen postseason success in decades.

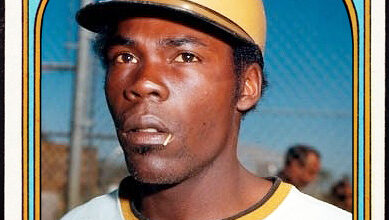

A prime example of such a team would be the Pittsburgh Pirates. The Bucco’s have been one of the most storied franchises in all of baseball. But the impossible glamour and charm we knew to be their championship teams in the ’60s and ’70s has since faded into a half century’s worth of cruel and disappointing outcomes.

In fact, since their last World Series title in 1979, they have managed to tally 13 seasons in which they won less than 70 games.

They have undergone an impressive turnaround mostly due to their farm system. Obvious evidence of that has been the rise of Andrew McCutchen.

But what of Jameson Taillon? It wouldn’t be inconsiderable to say that the young right-hander for West Virginia Power (single-A) will be the next ace of an organization that has suffered through years of despair.

Taillon was Pittsburgh’s first-round draft pick, and the second selection overall of the draft. The sole fact that Bryce Harper was the first player drafted should speak to the ceiling, or lack thereof, for Taillon with the Pirates.

The 6’-6”, 20-year-old is comfortable sending his fastball in the high 90s with plus movement. That’s always nice to have in a prospect, but what makes Taillon’s repertoire so malevolent is the command with which he delivers the draft’s best curveball.

The high-velocity fastball and hammer-drop curveball have been one of the game’s more dominating combinations. Fellow Texan’s Josh Beckett and Nolan Ryan come to mind. Both of whom adopted the fastball-curve combination in favor of the more conventional fastball-changeup offering.

Ryan, Beckett and Taillon all utilize similair strategies, because they unanimously agree that the greater disparity between velocity and movement comes from the violence of the curveball’s spin, forcing hitters to not only sit-back on the pitch when they were expecting something hot, but also readjust and reposition for the angle, not merely the downshift in speed.

The Lone Star State could possibly be on to something.

Look for Taillon and others to begin resurrecting understated and substandard franchises across the league. It won’t be long before baseball revisits the glory of years past.