It seems to be a popularly held notion that when Branch Rickey parted ways with the Brooklyn Dodgers and joined the Pittsburgh Pirates as their general manager, he knew the Dodgers were hiding a young potential superstar by the name of Roberto Clemente in their minor leagues and made the Dodgers pay for forcing him out by drafting Clemente away in the Rule 5 Draft.

It makes for a nice story, all right. The problem with it is that it doesn’t add up. Rickey sold his interest in the Dodgers, resigned as their president, and joined the Pirates in 1950. The Dodgers signed Clemente as an amateur free agent in 1954 and the Pirates drafted him later that year. So what’s the real story? For that, we have to go back to 1951.

The Dodgers’ workhorse

Don Newcombe was tired. The big Dodger right-hander had just pitched eight innings in game three of the 1951 National League playoff against the rival New York Giants. With a 4-1 lead, he didn’t dare ask out of the game. Regardless, removing him wouldn’t have entered the mind of Dodgers manager Chuck Dressen. That was simply not how it was done in 1951.

The Giants had been 13 games behind the Dodgers on August 11 before winning 37 of their final 44 games. This enabled them to tie the Dodgers for first place at the season’s end, forcing the special three-game playoff. (In 2001, Joshua Prager, writing for The Wall Street Journal, uncovered a sign-stealing scheme the Giants employed during this stretch. But that’s another story.)

With the archrival Giants breathing down their necks, the Dodgers leaned heavily on “Big Newk” down the stretch. In August and September, Newcombe had logged an astonishing 103 innings over 15 games, including 14 starts. Over the 11-day period August 23 – September 2, he made four starts, hurling 28 innings. On September 29, he pitched a complete game shutout against the Phillies in Philadelphia, only to come on in relief the next day in the eighth inning, exiting with two outs in the 13th.

The Giants win the pennant

Now on October 3 in the bottom of the ninth at the Polo Grounds, Al Dark led off with a single against Newcombe. Dressen inexplicably ordered first baseman Gil Hodges to hold Dark at first, guarding against a highly unlikely and foolish steal attempt. The next batter, Don Mueller, bounced a single through the spot where Hodges may have ordinarily been stationed. One out later, Whitey Lockman doubled to left-center field, scoring Dark, while Mueller sprained his ankle sliding safely into third.

While Mueller was being carried off the field and Clint Hartung was about to become perhaps the most famous pinch runner in the history of baseball, Dressen had a decision to make. Ralph Branca and Carl Erskine were warming up in the Dodgers bullpen. Dressen placed a call to his bullpen coach, Clyde Sukeforth, and asked which of the two was throwing better. Sukeforth reported that Branca was throwing hard while Erskine was bouncing his curve ball. Bud Podbielan, who had pitched to a 2.92 ERA against the Giants in five games, including a tidy ninth inning in game one, was not asked to warm up. Neither was Clem Labine, who had pitched a complete game shutout in game two the previous day. But Dressen had used Newcombe in relief in Philadelphia under similar circumstances, that time for almost six innings, as noted above.

Branca, a hard-luck loser in game one, entered the game to face Bobby Thomson. Every self-respecting baseball fan knows what happened next. Off Branca’s second pitch, Thomson hit a screaming line drive home run over the left field wall to win the pennant for the Giants.

Dressen covers his retreat

Sukeforth left the Dodgers after the 1951 season. He always insisted he had resigned rather than having been fired. Whatever the case, Dressen had publicly blamed him for the decision to bring Branca into the game to face Thomson. Sukeforth found staying with the Dodgers untenable under those circumstances.

Dressen was acutely aware that after losing the pennant-deciding final game of the 1950 season, the Dodgers fired manager Burt Shotton and third base coach Milt Stock, the latter for sending home a runner with the potential pennant-winning run, only to have him thrown out. (Yet another story for another time.) Surely he was anxious to deflect attention from his own questionable decisions: leaving a tired Newcombe in the game, failing to have Podbielan warm up, and holding Dark at first base. Eventually Dressen would be fired after the 1953 season after two consecutive World Series losses to the New York Yankees.

Sukey

Sukeforth was a baseball lifer, a catcher for the Cincinnati Reds and Dodgers from 1926-34. He remained with Brooklyn as a minor league manager and later a major league coach/scout. He would come out of retirement to play in 18 games for the Dodgers in 1945 at the age of 43. In an era when baseball players had nicknames like “The Yankee Clipper” and “The Reading Rifle,” he was simply “Sukey.” When Dodgers manager Leo Durocher was suspended from baseball in 1947, Rickey thought highly enough of Sukeforth to offer him the managerial post. Sukeforth turned the offer down.

Naturally, a few weeks after Sukeforth left the Dodgers, Rickey hired him as a coach/scout for the Pirates. In 1954, when Rickey became interested in acquiring pitcher Joe Black, the 1952 Rookie of the Year who fell on hard times in 1953, he dispatched Sukeforth to the Dodgers’ minor league team in Montreal to scout Black. The Pirates never acquired Black, who would pitch three more years without great success, but Sukeforth’s trip across the border wasn’t wasted.

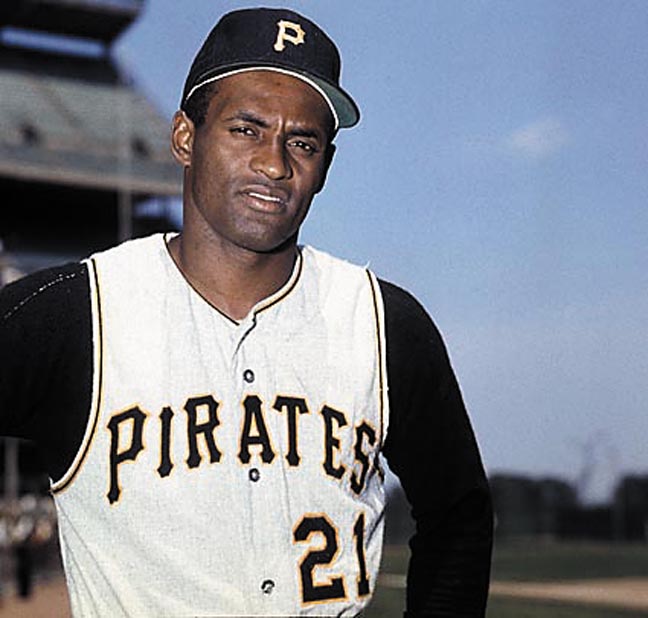

The Pirates discover Clemente

Sukeforth noticed another Montreal Royal named Clemente and came away impressed with the 19-year-old’s throwing arm, speed and bat. Despite having lost part of the sight in one eye as a result of a 1931 hunting accident, Sukeforth knew he was seeing a future star. He recommended Clemente to Rickey, who drafted the talented outfielder in that year’s Rule 5 Draft.

That’s right, baseball fans. The Pirates got Clemente thanks to Thomson and “The Shot Heard ‘Round the World.”