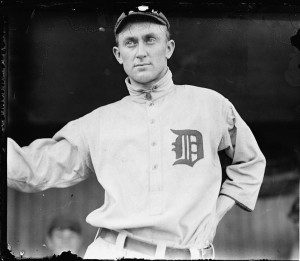

One hundred years ago this week, Detroit Tigers manager Hughie Jennings had a problem. One that was not at all of his making, either. A combination of factors had put him in a unique situation where he needed to field a major league team, and fast.

The story begins on May 15, 1912. Jennings and his Detroit Tigers were playing the New York Highlanders in New York. At the end of the sixth inning, an enraged Ty Cobb went into the stands and began attacking a fan name Claude Lueker, who had been taunting Cobb with racist language, including suggestions that he was of mixed racial origins.

This racial slur was too much for Cobb, and he savagely beat Lueker. The wall that exists between the players on the field and the fans in the stands had been breached, and the president of the American League, Ban Johnson, had seen the entire incident. He knew right away that something had to be done to address Cobb’s behavior.

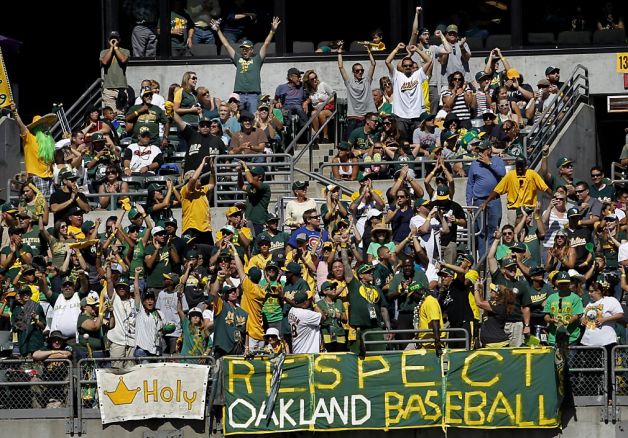

The Tigers left town after the game was over and traveled to Philadelphia to play Connie Mack’s Athletics. After a game between the Tigers and the Athletics, it was learned that Johnson had suspended Cobb indefinitely for going after the fan in New York. Cobb’s teammates on the Tigers voted to go on strike until Cobb was reinstated. It was the first successful players’ strike in major league history, and far from the last one.

On Saturday, May 18, a large crowd was expected to be on hand in Philadelphia’s Shibe Park. But the Tigers wouldn’t be able to field a team if the players made good on their threat. Ban Johnson, who had helped to create the situation by suspending Cobb, told the Tigers’ owner there would be a fine levied against the team if they could not take the field as scheduled.

The Tigers’ situation was precarious. It wouldn’t take too many forfeits to ruin the franchise financially, so something needed to be done. Enter Hughie Jennings and his friend Joe Nolan, a local sportswriter. They were tasked with hitting the streets of Philadelphia and finding players who would be replacement Tigers, if needed. It was almost as if they were asking “Hey, you. Want to suit up and play against the world champion Athletics today?”

Nolan and Jennings got in touch with Allan Travers, who was the assistant manager of the baseball team at nearby St. Joseph College. Travers had never actually played baseball before, but somehow wound up as the pitcher for the “Tigers” that day. Other replacements included Billy Maharg, who would later go on to help fix the 1919 World Series, and Bill Leinhauser, a noted amateur boxer. But none of them actually knew what they were in for just yet.

Cobb and his teammates, the regular Tigers, took the field as scheduled on that Saturday at Shibe Park. When Cobb was waved off, the rest of the Tigers followed suit, and the replacement Tigers were pressed into service. What resulted was a record-setting bloodbath, in which Allan Travers, who had never pitched a game before in his life, gave up 24 runs on 26 hits, which are records that will never be broken.

Travers’ batterymate that day was Deacon McGuire, who was catching the game at 59 years of age. Hughie Jennings also made an appearance in the game, along with Tigers coach Joe Sugden, who played first base. But it was Allan Travers who stole the show, in a manner of speaking.

Somehow, some way, Travers managed to record a strikeout during the Athletics’ offensive assault. Whoever the Athletics hitter was that couldn’t hit the college student — who had never pitched before — must have had a hard time living that one down. Travers later became a Catholic priest, and he remains the only priest to have appeared in a major league baseball game.

Philadelphia’s fans had protested the travesty they had seen on the field, and Ban Johnson knew this couldn’t be allowed to happen again. He threatened all of Detroit’s players (the regular ones, that is) with a lifetime ban if they persisted with their strike. Upon hearing this threat, Cobb insisted that his teammates should resume playing the next day, rather than sacrificing their careers on his behalf.

The Tigers did not play again until May 21 in Washington, and the teams’ regular players took the field in that game. Apparently what happened in Philadelphia stayed in Philadelphia, and the Tigers finished the season without further incident. Cobb eventually served a 10-game suspension, but he returned and won the seventh of his nine consecutive AL batting titles that season.

The Tigers saved their franchise, and Hughie Jennings was posthumously inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1945. But the legacy that he, and a ragtag assortment of college students and amateur boxers, left behind a hundred years ago in Philadelphia will never be equaled, in terms of sheer weirdness. There has never been, and will never be, another game like this one in major league history.