With the widely discussed Rule 7.13, Major League Baseball has finally moved to regulate the plate collision. Though the rule is long overdue, people are complaining. Complainants range from the old-school types who somehow think that freight-training catchers should remain part of a sport that doesn’t allow such contact anywhere else in the game, to folks who find the rule “confusing” and provides too many grey areas. First of all, it’s not confusing; it has contingencies. Contingent and confusing are not mutually inclusive. Here are the key points of Rule 7.13.

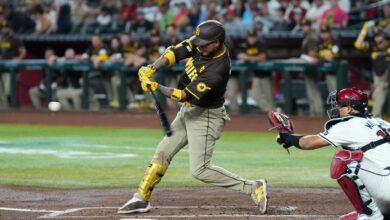

- A runner attempting to score may not deviate from his direct pathway to the plate in order to initiate contact with the catcher (or other player covering home plate).

- The failure by the runner to make an effort to touch the plate, the runner’s lowering of the shoulder, or the runner’s pushing through with his hands, elbows or arms, would support a determination that the runner deviated from the pathway in order to initiate contact with the catcher in violation of Rule 7.13.

- Unless the catcher is in possession of the ball, the catcher cannot block the pathway of the runner as he is attempting to score.

- Notwithstanding the above, it shall not be considered a violation of this Rule 7.13 if the catcher blocks the pathway of the runner in order to field a throw, and the Umpire determines that the catcher could not have fielded the ball without blocking the pathway of the runner and that contact with the runner was unavoidable.

The rule is pretty straightforward, and I’ve only left out a few phrases. Violating the above generally results in forfeiture of the run or the out, depending on who broke the rule, at the umpire’s discretion. The bottom line is this: You can’t go out of your way to initiate forceful contact. And if you make forceful contact, it has to be — to borrow from the rule books of other sports — a baseball play.

Sliding into home, you have to make an honest attempt to score without striking the catcher. If you’re a catcher and the throw is up the line, you have to make an honest attempt to catch the ball and apply a tag. No “none shall pass” nonsense, no Brian McCann machismo, and no Albert Belle open-ice body checks. Try to make a baseball play, and if the two of you run into each other, the umpire can decide if you were making an honest effort to score or prevent a run without clobbering the other guy. It’s really not that hard to grasp. In fact, it’s surprisingly well done for a first try, given the nature of the play it’s trying to regulate.

It isn’t as if sports officiating doesn’t involve judgement calls, and to the folks who think it’s too much for an umpire to determine, ask yourself this: Are you for or against the challenge flag? Because if you don’t trust an umpire to decide that a player went out of his way to block the baseline or jack up a catcher, then how do you argue for the “human element” where something tricky like balls and strikes are concerned? But I digress. The one part of the rule that might make it harder to call is this:

- A slide shall be deemed appropriate, in the case of a feet-first slide, if the runner’s buttocks and legs should hit the ground before contact with the catcher. In the case of a head-first slide, a runner shall be deemed to have slid appropriately if his body should hit the ground before contact with the catcher.

The play at the plate can involve a lot of moving parts and happen rather quickly. Sometimes it isn’t easy, on the fly, to tell what part of a guy hit the ground before a high-speed pileup, especially while you’re checking for the application of a tag and the secure possession of the ball as well as maybe whether a guy touched the plate before or after contact. Umpiring isn’t an easy job. That’s why the play is also subject to review. That’s why the challenge flag is another good new rule. But again, I digress.

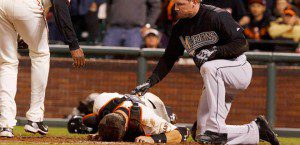

The pros of regulating the plate collision far outweigh the cons. The safety of players should be paramount, and if not for rules, sports wouldn’t be sports but instead a free-for-all. Rule 7.13 avoids situations like the one described by Orioles manager Buck Showalter:

“We’re talking about where the [catcher] is completely exposed, doesn’t have the ball and some guy hunts him. We’ve had it happen with Matt a couple of times. And as you remember, we were real unhappy about it. I can still remember the players who did it. With no intent to score. Had the plate given to him. Could have slid. And just [hit him] very maliciously.”

It isn’t just catchers who are being protected, but base runners as well. Catchers can be just as overzealous as runners when it comes to plate collisions, whether it’s machismo, settling a score, trying to prove their mettle, trying to make the team or trying to energize the bench. They’re the only defenders who are armored (yes, it’s plastic, but it’s plastic designed to protect them from fastballs and foul tips), and an armored shin dropped on a rotator cuff or slammed against an un-armored shin can lead to bad things.

Rule 7.13 is a relatively rare example of Major League Baseball getting something about right the first time. When your favorite players’ careers aren’t derailed or ended by football collisions, you’ll be glad. Eventually, it will have been long enough that people will wonder how the league ever allowed the plate collision to become so embedded in baseball tradition.