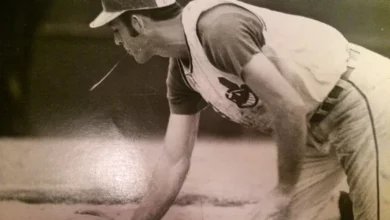

At the time, it was a big story. Ron Santo, the Chicago Cubs’ third baseman for 14 years from 1960-73, was traded across town to the Chicago White Sox on December 11, 1973. In return, the Cubs got catcher Steve Swisher and pitchers Steve Stone, Ken Frailing and Jim Kremmel, the latter added as a player to be named later.

A photo of White Sox general manager Roland Hemond with his arm around Santo’s neck, both men in 1970s-sytle wide-lapelled jackets, big-collared shirts and wide ties, all smiles, ran in the papers the next day. Alas, Santo would have little to smile about during his tenure with the White Sox.

“I thought about my parents.”

Earlier in December, the Cubs had worked out a deal that would have sent Santo to the California Angels in exchange for 23-year-old left-handed pitcher Bruce Heinbechner. However, Santo didn’t want to leave Chicago. Thus, he became the first player in baseball history to veto a trade under the then-new “10-and-5” rule. This gave any player with 10 years of service in the big leagues, five of which were with the same team, veto power over a trade. The White Sox were left as the only possible suitor. Heinbechner would die in an auto accident on March 10, 1974 while in spring training with the Angels. One can’t help ponder how his fate could have been different had the original deal gone through.

“To be honest,” Santo told Milt Richman of United Press International, “the thing I thought about was my parents being killed.” They had died in an auto accident in 1973.

“The best wrecking crew in baseball”

After a not-too-bad stat line of .267/.348/.440, 20 HR and 77 RBIs in 1973, Santo was joining an already-powerful lineup that featured Dick Allen, Bill Melton, Ken Henderson, Carlos May, Buddy Bradford and Jorge Orta. Allen was the American League MVP in 1972, when he hit .308/.420/.603, 37 HR and 113 RBIs, all league-leading totals except for the batting average. Melton led the league with 33 home runs in 1971. “It’s the best wrecking crew in baseball,” said White Sox manager Chuck Tanner to Al Abrams of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Fans and scribes alike thought the White Sox had a decent shot at unseating the Oakland A’s, World Series champs the previous two years, from atop the West Division.

But where to play Santo? Melton played third base. Tanner told Richman, “Ron Santo will be our designated hitter and bat sixth in the opener and Bill Melton will hit cleanup and play third base. No problem at all.”

Like days of old

On rare occasions, Santo looked like the Santo of old. On June 8 in Comiskey Park, he belted a grand slam off pitcher Bob Veale as the White Sox demolished the Boston Red Sox, 13-6. The next day against those same Red Sox, facing Bill Lee in the fifth inning, Santo swatted a deep drive over the head of left fielder Tommy Harper. Harper went back, hit his head against the wall and fell to the ground. There were no padded outfield walls in those days, because there were no multimillion dollar outfielders, either. Harper lay dazed, and before another fielder could retrieve the ball, Santo raced around the bases for an inside-the-park homer. In the seventh, he would touch up Lee for a more conventional two-run home run. Despite Santo’s heroics, the White Sox lost, 10-6.

Santo’s seventh-inning, two-run homer off the Kansas City Royals’ Steve Busby on June 24 decided a 3-1 road win. Busby was bidding for a second consecutive no-hitter until surrendering a single to Pat Kelly in the sixth inning. Then there was Santo’s seventh-inning, two-run, tie-breaking single against the A’s on August 1, to lead his team to a 7-3 win in Chicago.

But there weren’t enough of those moments from Santo in 1974. Perhaps it was an omen when the White Sox opened at home with the Angels — the same team for which Santo had declined to play — and got swept by scores of 8-2 and 3-2. It wasn’t to be for the 1974 White Sox, who finished a disappointing 80-80, for fourth place in the division. The pitching fell apart. There was an injury to Bradford, who also hit his head on an outfield wall, missing two months. Allen would abruptly retire in September. More on that later.

“Things got real screwed up.”

Santo was unhappy. He hated playing for Tanner and didn’t like being a designated hitter. When he played in the field, Santo was mostly used as a second baseman, which he didn’t like either. On the surface, moving a 34-year-old third baseman to second base didn’t make a lot of sense. Santo was a better third baseman than Melton. It would have made more sense to play Santo there and use Melton as the designated hitter. If you’re managing cardboard players on a Strat-O-Matic team, that’s what you do. But Tanner was managing people. He wasn’t going to change Melton’s role after all Melton had done for the White Sox. Besides, it wasn’t as if Santo were replacing a defensive wizard in Orta at second base. Orta would commit 18 errors there and finish below league average in several defensive metrics in 1974.

Finally, Santo and Allen were feuding. Santo was seen as a cancer in what was previously a harmonious clubhouse. Allen didn’t care for the way Santo antagonized certain young players on the team. In his book Crash: The Life and Times of Dick Allen, Allen wrote, “Things got real screwed up on the field and in the clubhouse” after the White Sox acquired Santo. “Santo thought himself a Chicago institution because he played across town with the Cubs. He thought he should be the team leader automatically. But you don’t get to be a team leader through longevity. Santo had all our guys screwed up.”

“He marches to a different drummer.”

Allen had been a controversial figure throughout his career. He was known to skip batting practice regularly and was often late to the ball park. He was a heavy smoker. Opinions of him differed. In Ball Four, Jim Bouton‘s diary of the 1969 season, he wrote, “There was a rumor abroad in the land that the Astros were going to get Richie Allen [as he was then known] from the Phillies and some of the Astros were against it. They said he’s a bad guy to have on a ballclub . . . If I could get Allen I’d grab him and tell everybody that he marches to a different drummer and that there are rules for him and different rules for everybody else. I mean what’s the good of a .220 hitter who obeys the curfew?”

Tanner obviously felt the same way. He and Sparky Anderson were the first of a new breed of managers who had different rules for their stars. Tanner and Allen came from small towns in Western Pennsylvania just eight miles apart, Tanner from New Castle and Allen from Wampum. (Finishing his career with the A’s in 1977, Allen wore “Wampum” on the back of his uniform instead of his name.) Having been traded after the 1969 and 1970 seasons, Allen didn’t want to report to the White Sox when he was dealt there after the 1971 season. So Tanner phoned Allen’s mother. They bonded over their similar backgrounds, and she convinced Allen to go to Chicago.

In Chicago, Tanner let Allen do things his own way, even asking him sometimes whether he felt like playing. Allen produced for the White Sox but his habits likely didn’t sit well with the old-school Santo. Over an eight-year period, Santo averaged 160.875 games played, including 1965 when he played 164 games in a 162-game season. (That’s not a typo.) Finally, Allen had enough and retired on September 14. Despite not finishing the season, he led the league with 32 homers.

Check your oil?

Santo’s final stat line with the White Sox was an anemic .221/.293/.299, 5 HR and 41 RBIs. Santo retired on December 12, walking away from the final year of his contract and a six-figure salary. He left baseball so he could take a job as vice president of sales for a Chicago oil company. As I type these words, I can’t help but think of the Seinfeld episode where George decides to pose as an architect. Jerry tells him, “I don’t see architecture coming from you.” Similarly, I didn’t “see oil” coming from Santo. Then again, I didn’t know him personally. For all I know, maybe he was a budding T. Boone Pickens. As you know, Santo became a radio broadcaster for the Cubs in 1990 until his passing in 2010.